For years, protest signs staked in Peoplestown front yards, fittingly painted in the red-white motif of stop signs, have carried phrases such as, “Stop Predatory Use of Eminent Domain,” “Legacy Residents Deserve to Stay in ATL,” and “Mayor Bottoms Stop Displacing Black Families.”

But that well-publicized friction between the City of Atlanta and a holdout contingent of Peoplestown residents hellbent on staying put in their homes appears to be over. The purchase and removal of houses on a block in the center of the neighborhood has been called necessary by city officials determined to curtail flooding issues—and decried by others as gentrification run amok.

Atlanta Mayor Andre Dickens’ office announced Monday the city has reached “breakthrough agreements” with Peoplestown residents that will allow for a “critical sewer infrastructure capacity relief project” to solve sewer overflows and flooding problems that have long plagued sections of Southeast Atlanta.

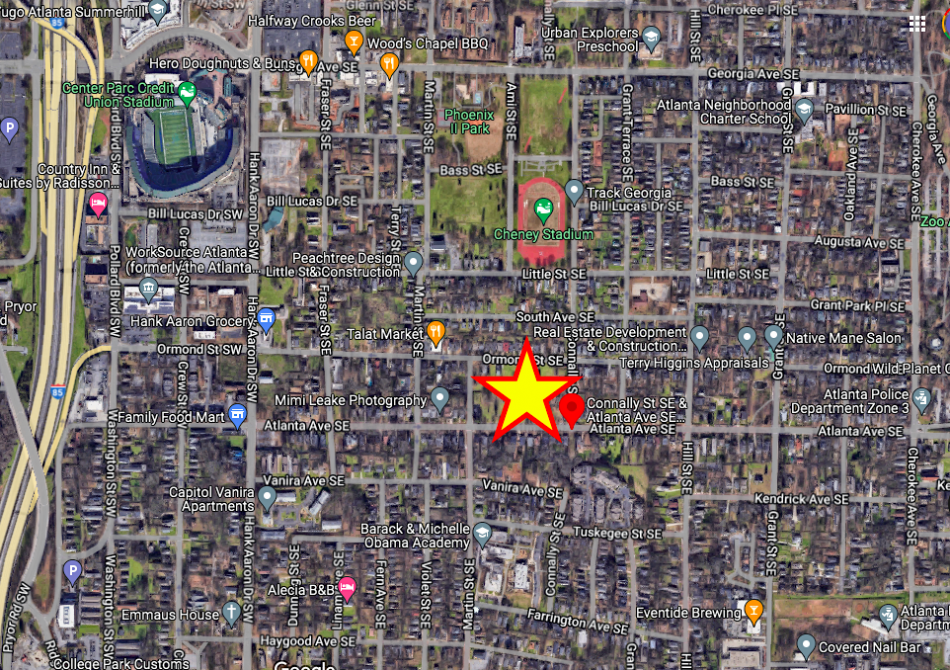

The area in question boils down to a single block in Peoplestown, located about four blocks from Georgia State University’s Center Parc Stadium and south of Summerhill. Grant Park’s The Beacon district is just southwest of the block in question, which is bounded by Atlanta Avenue, and Connally, Ormond, and Greenfield streets.

The Peoplestown block in question and its proximity to area landmarks such as Center Parc Stadium and Summerhill's Phoenix II Park. Google Maps

The Peoplestown block in question and its proximity to area landmarks such as Center Parc Stadium and Summerhill's Phoenix II Park. Google Maps

On Monday, the Atlanta City Council unanimously authorized final settlement deals, as negotiated between Dickens and three remaining families that owned homes where the infrastructure project needs to be built. Properties on the block also include those that city officials had previously acquired and others covered by an agreement Dickens negotiated in June, per the city.

During his first year in office, Dickens has met with impacted Peoplestown residents multiple times throughout the negotiations, city officials said. Terms of deals the city struck with remaining residents haven’t been disclosed.

“I have spent this year listening to Peoplestown residents, working directly with the most-impacted families, and charting a course that will allow us to move forward in a way that is in line with our values and fulfills our obligation to alleviate the challenges that have plagued Peoplestown,” Dickens said in a press release. “I know these families wanted to stay in their homes, and I am grateful for the sacrifice they are making for the larger community and our city.”

The infrastructure project—expected to create a pond and park as a functional neighborhood amenity—is considered critical for the city’s obligations, under two federal consent decrees signed in 1998 and 1999, to upgrade its sewer infrastructure and water quality.

City officials say it’s designed to solve overflows from a combined stormwater and sewer system in Peoplestown that has jeopardized public health and safety.

An Atlanta Avenue home that's part of the city's new agreement, as seen in December with protest signs dotting the front yard. The previously cleared land in question is at left. Google Maps

An Atlanta Avenue home that's part of the city's new agreement, as seen in December with protest signs dotting the front yard. The previously cleared land in question is at left. Google Maps

Tanya Washington, a Georgia State University law professor who’s been at the center of the controversy for a decade as she fought to remain in her century-old bungalow, said she hopes the outcome will motivate other communities “to stand up for themselves and inspire responsible exercise of authority by those in power.”

“It is clear that the city will move forward with its plans, and that makes it reasonable to seek a satisfactory resolution,” Washington said in a statement. “My disappointment is curbed by the respect and integrity Mayor Dickens has shown in how he has dealt with us and this issue he inherited.”

The family of the late Mattie Jackson—a civic leader, mayoral advisor, and Peoplestown “legend” who once represented Atlanta by bearing the 1996 Centennial Olympic Games torch—called for a memorial to honor Jackson where her home once stood on the block.

Jackson died at age 98 two years ago this month, having fought for years to spare her house from eminent domain.

“The struggle to remain in our home over all these years, a home that [Jackson] loved and cherished, was devastating to the family. Today that chapter is closed,” the family’s statement reads. “We hope the city will find some fitting way to honor our matriarch, Mattie Jackson, in the public space that will be developed on the ground where she lived, raised her family, and so ably served the City of Atlanta. That would be a fitting last chapter for her legacy.”

Department of Watershed Management officials expect to initiate the procurement process for the infrastructure project soon, and to start construction sometime next year.

• Photos: Georgia State's convocation, basketball, concert arena has risen (Urbanize Atlanta)