In the following Letter to the Editor, Hugh Malkin, Midtown Neighbors’ Association Infrastructure Chairperson and an Atlanta tech entrepreneur, details the true cost of the city’s lack of public swimming facilities. He also posits that a recent setback in Virginia-Highland is emblematic of broader problems and offers potential steps toward solutions.

His suggested title: “Drowning in Disparity: How Atlanta's Aquatic Deficit Threatens Our Children.”

...

Dear Editor:

Drowning remains a leading cause of death for children, a stark tragic reality underscoring a critical issue in Atlanta's severe “aquatic deficit.”

This deficit refers to a glaring absence of accessible swim facilities and water safety education in the city. It also contrasts sharply with Atlanta’s vibrant suburbs, where summer swim teams dot nearly every neighborhood.

Yet within Atlanta's dense Beltline corridor, 45 neighborhoods share only one public summer swim team. That’s right—one.

This disparity isn’t just about missing out on fun. It’s a serious safety crisis. As a parent and lifelong swimmer, I’ve experienced this shortage firsthand.

Quick History: Atlanta's Disappearing Pools

To understand Atlanta’s current aquatic shortfall, we need to examine its past. Hannah Palmer, in her book and art installation Ghost Pools: A brief history of swimming in Atlanta and across America, uncovered a forgotten legacy. Atlanta was once known as “the swimmingest city in the country,” boasting numerous public pools that were thoroughly enjoyed by residents.

However, this legacy unraveled starting in the 1950s. Palmer's research reveals that as pools began to desegregate, many white swimmers abandoned them. This led to a decline in city commitment, drying up funding, and the eventual closure or disrepair of public pools, creating “aquatic deserts.” That is, communities with little to no access to swimming facilities.

This history has a measurable impact today on swimming proficiency, especially among different racial groups.

National studies show significant disparities: 64 percent of Black children, 45 percent of Hispanic/Latino children, and 40 percent of White children have low to no swimming skills. Such statistics highlight a critical safety concern, placing these groups at a much higher risk of drowning.

Current Landscape, Proposed Solution

This historical shadow continues to affect Atlanta today. Atlanta Public Schools and City of Atlanta officials are falling short in meeting the community’s aquatic needs. Opportunities for water safety education and team swimming are notably absent in many of Atlanta’s dense urban areas.

An ideal solution involves the city’s Department of Parks and Recreation collaborating with APS to establish a summer swim team league. Both organizations share a commitment to equity and community wellbeing: DPR's “Activate ATL” plan focuses on addressing disparities in “historically underserved parks,” and APS Athletics emphasizes equity and inclusivity. This shared vision provides a strong foundation for collaboration.

An important note: For a neighborhood swim team, an eight-lane, 25-yard pool is the optimal facility, serving as the official standard for competitions. Eight lanes ensure efficient competitions and effective practice management. Safety requires a minimum depth of four feet at the starting end, though six to seven feet is highly recommended for modern facilities. An “L-shape” design with a shallow area maximizes utility for both competitive training and lessons.

While most Atlanta high schools have access to a district pool for a swim team, Midtown High School is a notable exception. It currently lacks a city pool large enough for a swim team.

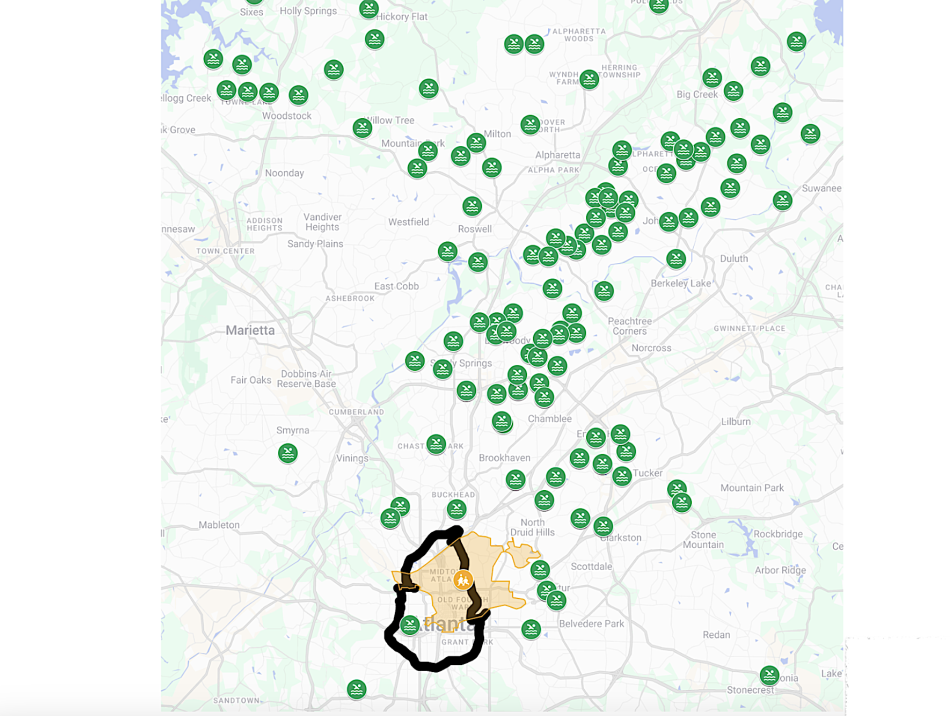

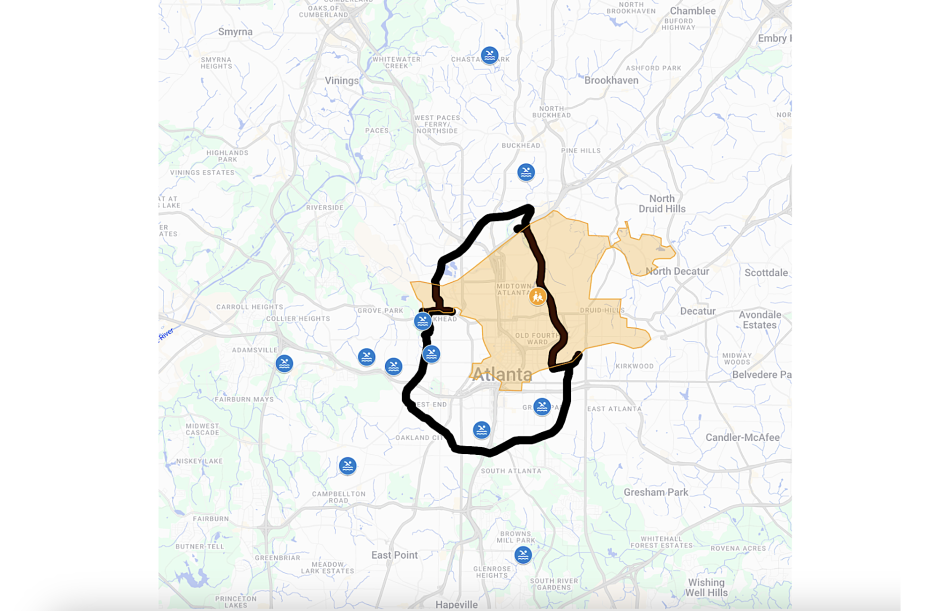

City pools capable of hosting a summer swim team showing none in the Midtown High School district.Contributed

City pools capable of hosting a summer swim team showing none in the Midtown High School district.Contributed

Recent Setback: Va-Hi Pool Project

Recognizing this void, parents from Virginia-Highland Elementary formed the Virginia-Highland Pool Association in hopes of building a year-round community pool on an underutilized APS field. [Editor’s note: The APS-owned site considered perfect by neighbors is a grassy property at the southeast corner of Virginia Avenue and Ponce de Leon Place, diagonal from Virginia-Highland Elementary School. It’s colloquially called “The Field of Dreams.”]

Va-Hi's so-called "Field of Dreams," at right, as seen along Virginia Avenue in winter 2023. Google Maps

Va-Hi's so-called "Field of Dreams," at right, as seen along Virginia Avenue in winter 2023. Google Maps

This project aimed to teach life-saving swimming skills to APS students and host a much-needed neighborhood summer swim team. Placing the pool on APS property offered a unique opportunity for community benefit and integrating water safety education.

After extensive discussions, VHPA and APS drafted a pre-development agreement. This was intended as the foundational first step for VHPA’s multi-year fundraising and design.

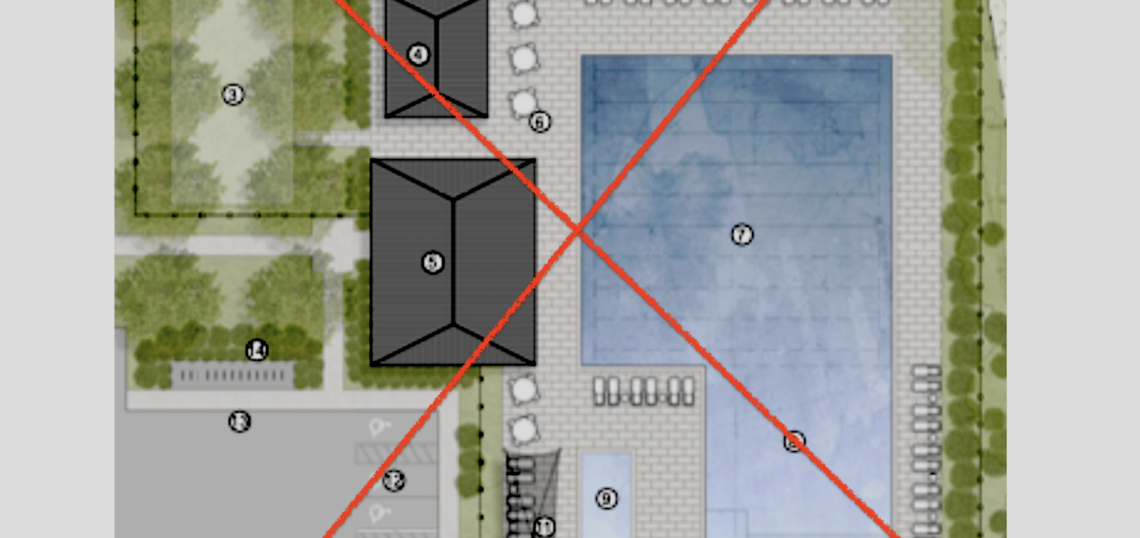

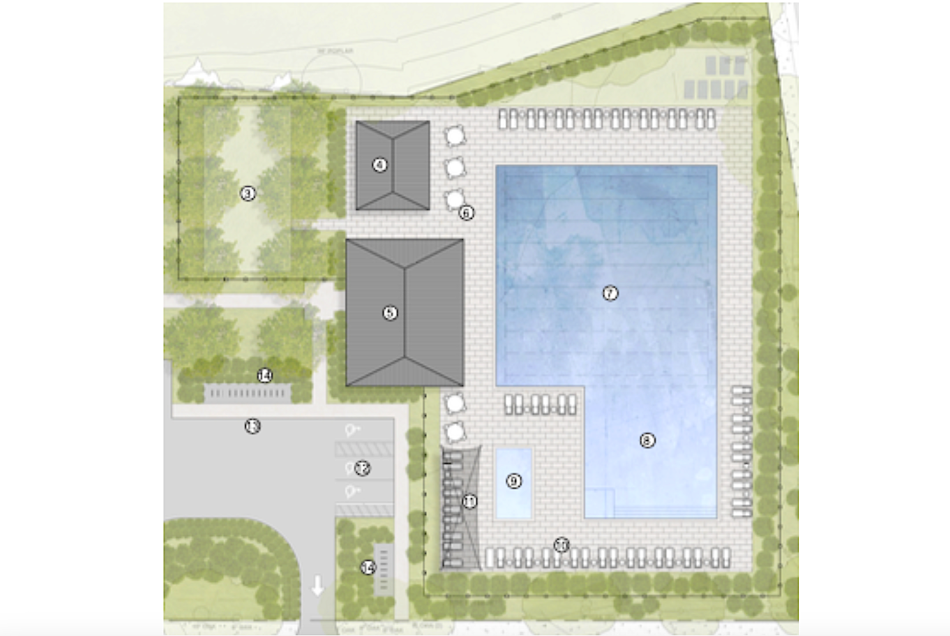

Proposed but shelved Virginia-Highland pool site plan. Courtesy of Virginia-Highland Pool Association

Proposed but shelved Virginia-Highland pool site plan. Courtesy of Virginia-Highland Pool Association

However, the Virginia-Highland Civic Association, a volunteer-run neighborhood organization, viewed this as their final formal opportunity for critical community input. At a town hall in April, residents voiced opposition, primarily citing street parking concerns. This mirrors urban planning professor Donald Shoup’s warning that debates over “free” parking often derail higher-value public projects by prioritizing individual convenience over collective benefit.

While parking concerns were prominent, the VHCA's unanimous non-support for this version of the agreement was rooted in a commitment to fair procedure and thorough project vetting.

The community pool project has since been shelved, with APS formally ending the proposal on May 28. APS’s decision was influenced by neighbor concerns, VHCA’s stance, and APS’s other possible uses for their land.

The project ultimately fell into a procedural “chicken-or-the-egg” trap. VHCA, a volunteer group, expected detailed plans upfront, which VHPA could only produce after an initial agreement allowed fundraising.

As Ezra Klein argues in his book Abundance, legal and procedural hurdles often obstruct necessary infrastructure. This vision succumbed to the combined impact of a vocal minority and procedural complexities, leaving Virginia-Highland and the wider Midtown High School community still without public pools capable of hosting swim teams.

2 Cents: Recommendations for Future Projects

If Atlanta is to build essential public amenities, the approval process itself must be reformed through a collaborative approach.

DPR and APS Athletics are well-positioned for this, given their overlapping missions focused on equity, youth development, and community safety.

Based on this experience, here's a framework, in my opinion:

- Establish a “Public Benefit” Fast Track: The City of Atlanta should create a streamlined approval process for non-profit, public-benefit projects, differentiating them from commercial developments.

- Solve the “Chicken-or-the-Egg” Problem: APS must establish a predefined process for partnerships with nonprofits, potentially offering seed grants or technical assistance to help groups create preliminary plans. This breaks the stalemate where money can't be raised without an agreement, and an agreement can’t be reached without costly plans.

- Set Clear Decision-Making Criteria: Approving bodies should use a clear, publicly stated rubric for successful proposals to shift debates from subjective complaints to objective questions. This prevents solvable issues like parking from derailing life-saving projects.

- Develop “Off-the-Shelf” Plans: DPR should create pre-designed, pre-vetted plans for community pools. This lowers the barrier for volunteer groups, who could propose implementing a city-approved version. DPR, MARTA, and APS should identify pre-approved sites for city-wide swim teams.

- Create a Public Project Accelerator: A city agency should act as a partner and guide for volunteer groups, providing coordinated legal, architectural, and fundraising expertise, treating nonprofits as partners in building public abundance. This accelerator would foster vital public amenities and lead to a more resilient Atlanta.

The failure of the Virginia-Highland pool project highlights a critical issue: Atlanta's severe aquatic deficit and our city’s difficulty in providing essential public resources.

Drowning remains a real concern, and the glaring absence of accessible swim facilities, especially near the dense Beltline corridor, is a significant safety crisis that demands immediate action. We’ve seen how bureaucratic obstacles and vocal opposition can hinder progress, but we also recognize a clear path forward.

It’s time for DPR and APS to act on their shared commitment to equity and community well-being. We specifically call on them to collaborate immediately to establish a public summer swim league comparable to those in the suburbs. Furthermore, they must identify a suitable site within the Midtown High School district and construct a suitable pool, as outlined above.

This crucial investment will provide a life-saving outlet for our children ages 5 to 18, benefiting them today and for generations to come. This isn't merely about recreation; it's about public safety and fostering a more resilient and equitable Atlanta.

...

Follow us on social media:

Twitter / Facebook/and now: Instagram

• Letters to the Editor (Urbanize Atlanta)