After listening to Caleb Stubbs passionately discuss his pipe-dream vision for the future of rail transit across metro Atlanta, a reporter suggests his ideas are both grandiose and logical enough to make him sound like the late-1990s version of Ryan Gravel, the Georgia Tech grad student who invented the Atlanta BeltLine.

Only instead of pitching a single, multi-use BeltLine trail on former railroads around Atlanta’s core, Stubbs envisions underused space in such corridors becoming a vast web of two-way commute options, zipping residents across the metro by the thousands, and bypassing so many chronically clogged interstates and highways.

Stubbs, in his laidback Mississippi drawl, chuckles at the “Ryan Gravel of Trains” comparison. But it could be apt. By day, he’s a young transit and rail engineer at Kimley-Horn, a leading design and planning consultation firm on all aspects of cities. By night, he dreams. And his ideas for a transit system that’s both comprehensive and financially viable, while nascent, are laid out in a detailed, 146-page report that’s starting to gain an audience with people in powerful places, from BeltLine boardrooms to the halls of Congress.

The time to get the proverbial wheels moving on “ATL Trains”—Stubbs’ simple name for such a grand vision—has never been better than now, he believes. And in ways beyond sheer scope, the transit mode blueprint he’s spent years compiling and refining is different than anything that’s emerged before in metro Atlanta, where bold transportation ideas (with the exception of MARTA) traditionally come to die.

“Commuter rail itself, just as a general idea, is not anything new—it’s been studied many times,” says Stubbs. “But really, I think what sets ATL Trains apart is the level of detail, as well as the financial feasibility aspect of it.”

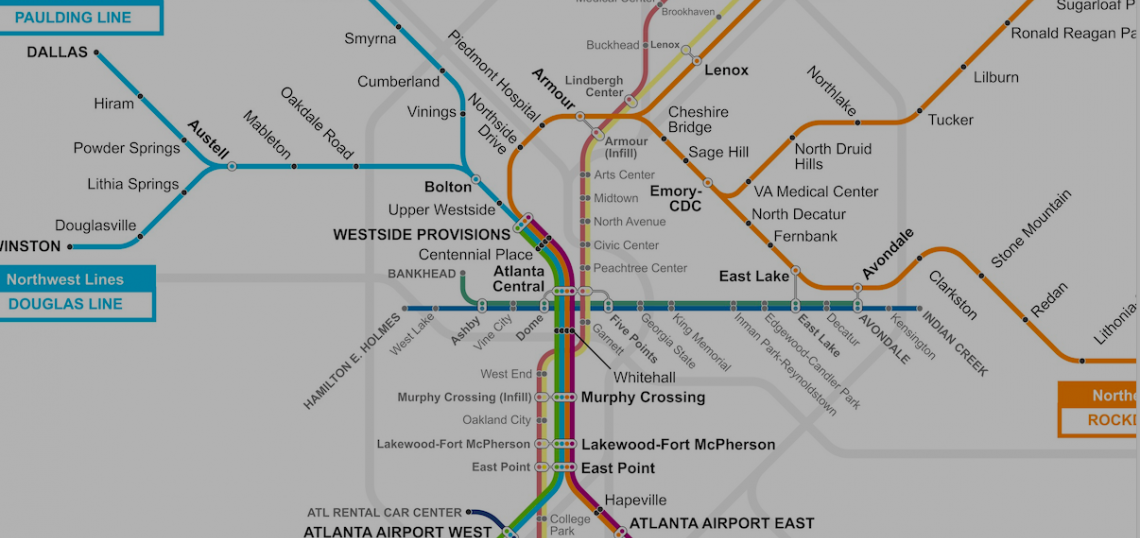

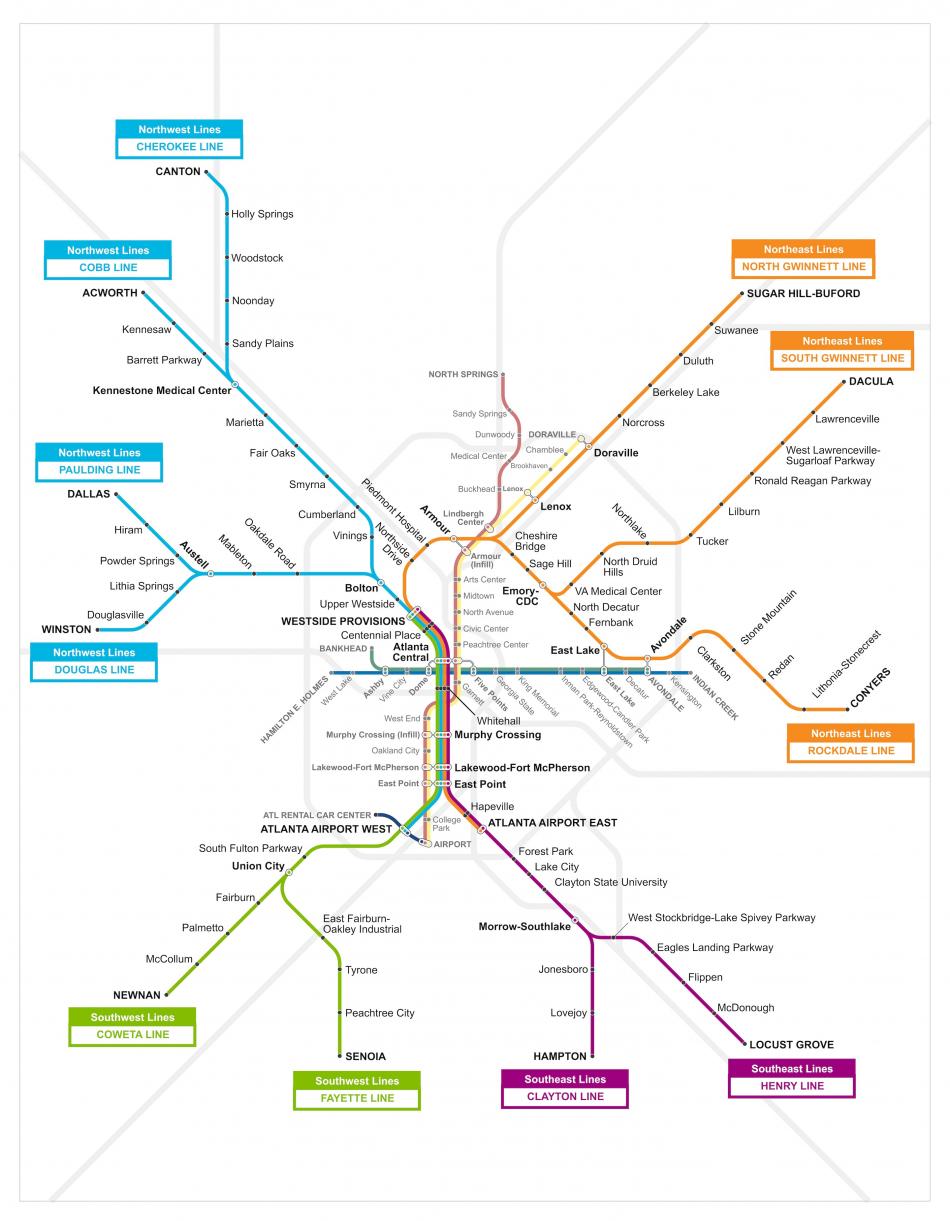

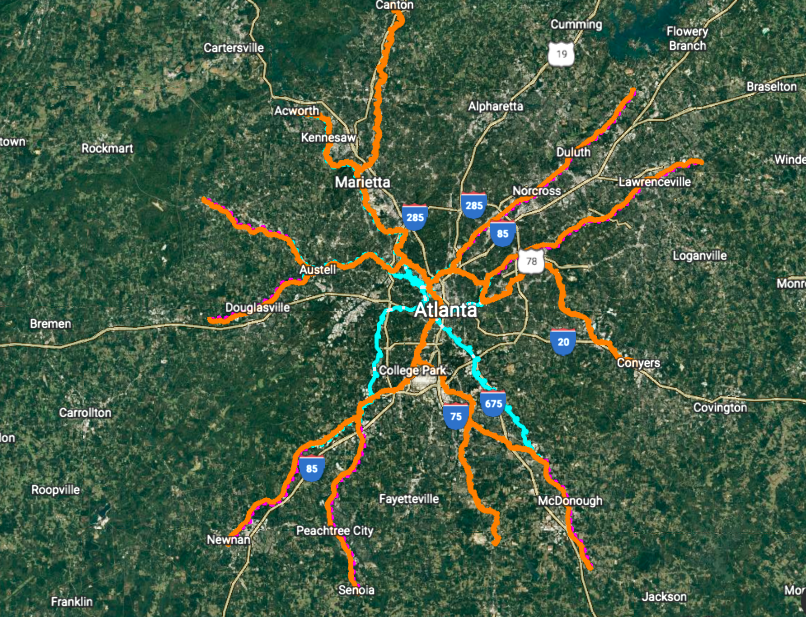

The aerial overview of a hypothetical regional commuter train network in existing railroad right-of-way. Courtesy of Caleb Stubbs/ATL Trains

The aerial overview of a hypothetical regional commuter train network in existing railroad right-of-way. Courtesy of Caleb Stubbs/ATL Trains

Stubbs, 28, was born in suburban Atlanta’s Douglasville but grew up mostly in northern Mississippi. He describes himself as a “transit nerd” who doodled train maps as a kid, thought of ways to expand transit systems, and dreamed of one day returning to Atlanta. In 2017, freshly graduated from Mississippi State University with a degree in civil engineering and a job at Kimley-Horn, that’s what he did.

A turning point for the rail enthusiast came in 2018 with the passage of Georgia’s HB 930. That legislation created the Atlanta-Region Transit Link Authority, or ATL, which oversees a 13-county metro area and lends promise that the region’s notoriously balkanized transportation jurisdictions and agencies might find common ground in one place, together. The 16-member board has something unique in the history of Georgia: the power to design, construct, and maintain a truly regional transit system, within its 13-county boundaries. (Stubbs’ vision calls for The ATL to ultimately act as the transit system’s operator.) Just as crucially, the HB 930 transit law’s SPLOST created in 2018 can provide a means of generating local funding to help pay for such a far-reaching system.

“Previously, there’s not been a way—short of lobbying the state legislature—to really implement a dedicated transit revue outside of the transit counties,” Stubbs says. “Now, there is. Many counties can opt in unilaterally for an up to 1-percent sales tax for 30 years.”

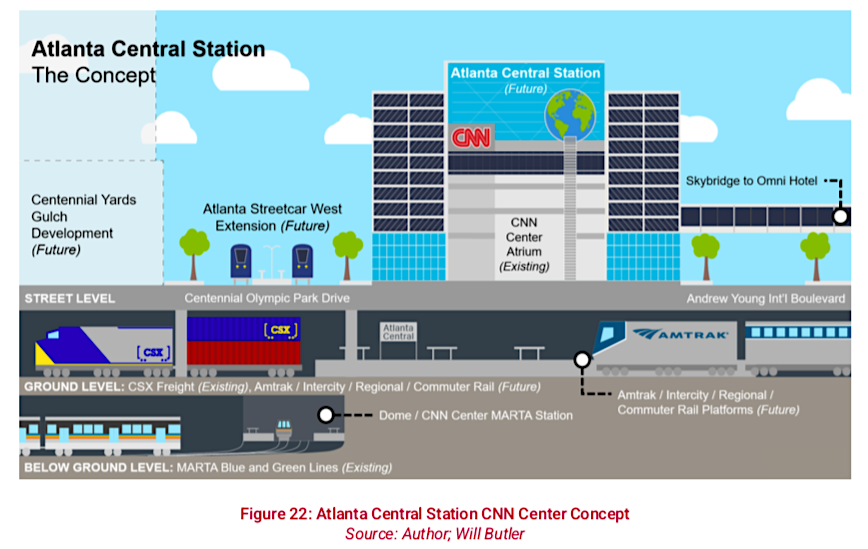

All of that got Stubbs thinking about existing rail corridors—and how the state hadn’t conducted anything resembling a comprehensive commuter rail study since 2007, despite several stops and starts. (Remember the “Brain Train” idea between Atlanta and Athens? Or the Lovejoy line concept that scored millions in federal earmarks but never laid a foot of track? Or the mammoth, multi-modal, never-happened transit hub envisioned for the Gulch, like Atlanta’s answer to Grand Central Station?)

In 2019, Stubbs began studying the bones of Atlanta’s existing rail corridors in his spare time. Freight volumes, the placement of tracks, current railyards, how it all flows together as a network. When the novel coronavirus cast a pall over the world a year later, relegating society to its makeshift home offices, Stubbs’ focus went from diligent to borderline obsessive, he jokes, and the title of his “COVID project” was born: ATL Trains.

The lightbulb moments kept coming.

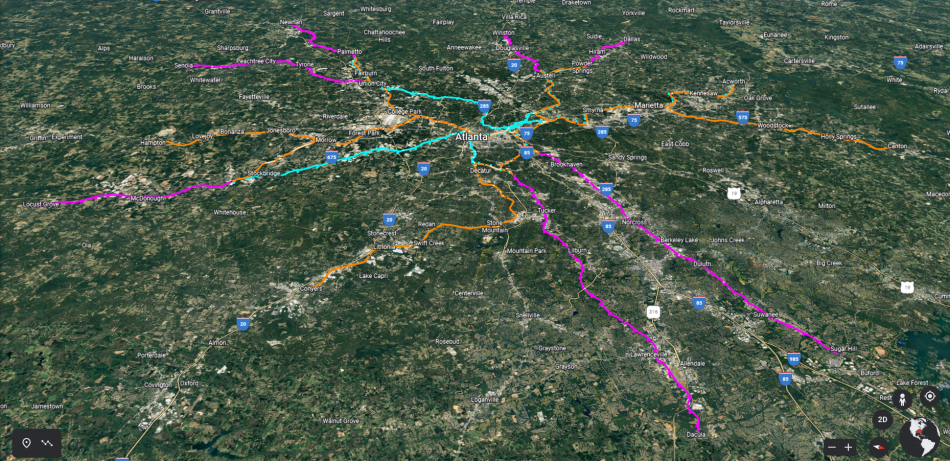

What became immediately clear to Stubbs, in his estimation, is that today’s railroad corridors contain some of the most underused right-of-way in Atlanta and the broader region, in terms of how wide they are. Upwards of 80 percent of metro Atlanta’s rail network consists of corridors with a single track. ATL Trains calls for commuter rail services increasing those routes to at least two tracks, if not three or four tracks.

“Almost all corridors in the Atlanta region are at least 100-feet wide,” says Stubbs. “Yet a single-track only requires 20 feet of right-of-way. Even with those corridors that are proposed to be four-track [in the ATL Trains concept], they can fit very comfortably in the existing right-of-way along almost every line.”

As seen looking southwest across Gwinnett County, the colors designate whether ATL Trains concept lines would be designed exclusively for freight (blue), for passenger rail only (orange), or a mix of both (magenta). Courtesy of Caleb Stubbs/ATL Trains

As seen looking southwest across Gwinnett County, the colors designate whether ATL Trains concept lines would be designed exclusively for freight (blue), for passenger rail only (orange), or a mix of both (magenta). Courtesy of Caleb Stubbs/ATL Trains

About those routes. Historically a railroad hub, Atlanta (original name: “Terminus”) has an advantage in that many suburban population centers of today were formerly outlying towns literally built on the railroads, with train lines still bisecting city centers that have flourished in recent years—or that have the potential to rapidly grow. The spokes of the wheel, so to speak, are already there, as Stubbs sees it.

Fleshing those corridors out into ATL Trains would call for an 11-line system spanning 300 miles, with 88 stations dotted along routes that would octopus out in almost all directions. (For context, that’s about six times the size of MARTA’s current heavy rail system, with more than twice the number of stops.) The system would be so comprehensive, according to Stubbs’ research, 83 percent of the region’s 6.1 million people would live within five miles of it. And more than half of the metro’s jobs would be within a mile of commuter train access.

Stubbs estimates between 28 and 55 million people would annually ride ATL Trains, ranking it as no less than the sixth-most patronized system in the country, somewhere between Chicago’s Metra and San Francisco’s Caltrain. Twelve of the 13 counties within the project’s scope already have access to at least one freight corridor—the anomaly being fast-growing Forsyth County, where alternate transit modes would have to be explored. That means lines would cover cities from Sugar Hill and Buford in Gwinnett County, around clockwise to Conyers in Rockdale, down to Senoia in Coweta, around to Acworth in Cobb (with a stop near the Braves’ Truist Park included), and finally up to Canton in Cherokee.

A few aspects of the concept are crucial to its success and shouldn’t be negotiable, as Stubbs sees it.

Trains should be bi-directional and operate all day, with hourly frequencies at most, as opposed to more limited services the Georgia Department of Transportation has previously studied that called for roughly three roundtrips per day, in mornings and evenings. Anything less, says Stubbs, would be too limited, as today’s riders would want to use the system to connect to activity centers across the metro, and not just a more standard ’burbs-to-downtown service.

Also, all lines must at least provide service to downtown Atlanta, if not terminate there, as analyses and ridership models prove; and as opposed to hypothetical lines put forward in previous studies, says Stubbs, each route would also have to connect to the airport, lending riders across the metro the option to leave vehicles at home or avoid costly ride-share services when catching flights.

Which brings us to the snarling, 300-pound gorilla in the room: projected costs.

Stubbs estimates that building out the full system (excluding Forsyth County, where proper freight corridors don’t exist) would cost in the ballpark of $16 billion. That amount includes funding for sweetening the deal for railroad companies by investing in upgrades for capacity improvements, as some railroad lines are maxed out today. His funding models don’t rely on the State of Georgia to contribute a dime. Instead, the assumed funding mechanism would be a half-penny, 30-year transit SPLOST for the dozen counties served. There would be three exceptions, however, where transit spending is either currently capped by law (Fulton County) or where voters have previously approved tax-based transit spending (Atlanta’s More MARTA sales tax, and Clayton County’s full-penny sales tax for high-capacity transit.)

“That is shown to be financially feasible,” says Stubbs of his research. “In fact, with most counties, that just takes up a fraction of that half-penny, so most counties would have enough left over to do other things as well.”

Those estimates, however, do assume a federal match amounting to half of capital costs to build out ATL Trains. (Once built, fares would cover 50 percent of the system’s operating costs, Stubbs estimates.) At the federal level, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act—a recently passed, bipartisan investment over the next five years—is set to include between $44 and $87 billion in new funding for regional rail networks that isn’t available to other transit modes, equating to what Stubbs sees as the most opportune time in recent memory to make progress. With its piece of that federal pie, Amtrak has expressed interest in building out a robust intercity rail project in Atlanta as its Southeastern hub; that activity, as Stubbs sees it, could make Amtrak a crucial ally in bringing ATL Trains to fruition.

“What’s different about regional rail, in contrast with heavy rail and light rail and [bus rapid transit], for that matter, is that regional rail is a truly open system,” says Stubbs. “The same tracks that carry regional rail just as easily carry freight and intercity trains.”

So far, Stubbs has worked with contacts in the industry to bring his ATL Trains concept before Atlanta Regional Commission officials, GDOT’s intermodal division, The ATL’s chief planning officer, and Anna Cullen, the transportation policy advisor for U.S. Sen. John Ossoff’s office. He also scored a brief, 15-minute time slot to present to Eamon Walsh, Amtrak’s federal director of government affairs. He’s been trying to schedule a sit-down this month, he says, with Atlanta-based Norfolk Southern to start conversations with train companies.

Official sources spoke to Urbanize Atlanta in general about how the hurdles (especially financial ones) to pull off a commuter rail system like ATL Trains would be monumentally huge—but in the same way that Atlanta attracting the Olympics was once thought impossible, or creating the bustling BeltLine from weedy railroad beds prohibitively difficult.

Stubbs was most enthusiastic following his meeting with ARC. Officials privy to his plans there declined to comment, but the agency provided a one-sentence statement reading: “We are always eager to hear innovative ideas for addressing the region’s transportation challenges.”

In terms of a timeline, Stubbs estimates the ATL Trains system could be fully built out within a decade, but he concedes a galaxy of moving parts could impact that calculation. When asked earlier this summer how much time he’s devoted to ATL Trains—on a basis that could be called volunteer but is most definitely unpaid—he let out an exasperated sigh, did quick math, and finally said 800 hours, at least.

“It’s something I’ve always been passionate about, and I feel like as I’ve acquired skills over the years with regard to my job as a transit planning and transit rail engineer, it’s just been the right time,” says Stubbs. “My hope and desire from the start was always to just help reignite a conversation about commuter rail, about regional rail, and to get that ball rolling.”

[Correction: 12:11 p.m., Sept. 1. This article has been updated to reflect that Senoia is in Coweta County.]

• Alternative transportation news, discussion (Urbanize Atlanta)