STEVE Nygren, the visionary behind Serenbe and still very much its public face, is weaving a golf cart around snow-caused potholes on a chilly January evening, pointing out gorgeous horses, a herd of whitetail deer, and a gargantuan new modern-lodge house that’s costing in the ballpark of $10 million.

A born host, Nygren was raised the son of Colorado farmers. His professional roots trace back to Atlanta’s 1970s restaurant scene as cofounder of the country French bistro Pleasant Pheasant empire, which he sold in the 1990s. He still has classic movie star looks, like he could be riding shotgun next to Steve McQueen. Instead he’s bouncing around in the golf cart, beaming, and bursting with facts about a meticulously curated, rapidly growing exercise in New Urbanism he’s carved from pastures and forests, where about 1,200 people now live in 600 housing units and counting.

Twelve seconds at Serenbe and you know a humdrum subdivision or banal master-planned community—those hallmarks of metro Atlanta’s postwar population boom—this is not. One street could be Copenhagen, the next new housing in the Cotswolds. Serenbe’s latest commercial node is swelling with new businesses. Construction on a massive new hamlet—ironic as that may sound—is just getting started, with a central park at its core. Plus, to the delight of kids, Serenbe now has trampolines.

Counting infrastructure, Nygren estimates Serenbe is nearly a billion-dollar project at this point. Each week, new residents arrive. Around virtually every wooded bend is a crew putting up a new home, if not a row of them. The staggering architectural variety could make this a design-lovers Promised Land—or for naysayers, the most contrived, oddly utopian human habitation this side of The Truman Show. (Urbanists allergic to golf-cart lifestyles should also avoid.) Whatever your take, you can’t deny that what felt like a noble experiment with a farm-to-table, eco-conscious heart two decades ago (or even one decade ago) has morphed into a bona fide, multidimensional, thriving small town with Buckhead refinement. Down here, 35 miles southwest of Atlanta, living your best life isn’t just possible—it’s mandatory.

Nonetheless, about halfway through a two-hour tour, Nygren says something both humble and surprising: “Everyone in Atlanta just has no clue we’re here.”

What? Still?

This spring will mark 20 years since Serenbe officially opened and the first people who weren’t Nygren’s family or employees moved in. The original pitch, like the current one, is that it provides easy connections to nature and agriculture (good luck finding a fresher beet salad than what The Farmhouse restaurant serves) within a 25-minute drive of Atlanta’s globally connected airport. Through his restaurants, Nygren had developed a strong reputation intown; he stumbled on the original Serenbe acreage while on a country drive with his family in the 1990s, started cobbling together neighboring farmland and forests when rumors of development began swirling, and soon ditched his family's home on a 1-acre spread in Ansley Park. On the very first Serenbe street, Selborne Lane, Nygren initially offered a row of 30 houses. He thought contracts would trickle in, one at a time. Instead, the first 20 were under contract within 48 hours.

Apart from a slowdown during the Great Recession, when Serenbe’s four builders at the time were either idle or bankrupt, it’s been gangbusters growth ever since. On any given day, more than 200 construction crew members are swinging hammers around the various hamlets, part of 10 building companies on site now.

With the growth of housing and retail options (more than 30 businesses total), the sheer cost of calling Serenbe home has also ballooned. Nygren points to estate lots that are selling for north of $2 million—for the land alone, in the City of Chattahoochee Hills, in farflung South Fulton and Coweta counties. Apartments and condos are available, but new housing in even the $600,000 range (that’ll get two bedrooms in about 1,200 square feet) is increasingly rare. That hasn’t been a deterrent, however. New Serenbe homeowners have hailed from as far as Turkey, England, and Denmark, and many since the pandemic have flocked in from Los Angeles and New York. Still, about 70 percent of residents are from the Southeast (you’ll hear twang comingling with proper British dialect), and 80 percent of Serenbe denizens live here full-time without second homes, according to Monica Olsen, Serenbe’s chief marketing officer.

“As a resident,” Olsen notes, “[the growth] has been kind of amazing.”

So what’s working down here? What’s changed recently—and what’s coming? With Serenbe’s 20th anniversary on the horizon, we accepted an invitation recently to explore the community for the better part of a weekend. What follows is a photo log of what we found—beginning with the newest sections, and spanning from the deepest woods to the leather banquettes of dynamite new restaurant Austin’s—at a master-planned place like no other in the U.S., according to Nygren.

“I know that because everybody’s coming here from all over, and a lot of them never thought they’d live in the South,” he says. “[Other developers] have done the farm, the equestrian, the arts, the ag—but nobody’s done this.”

…

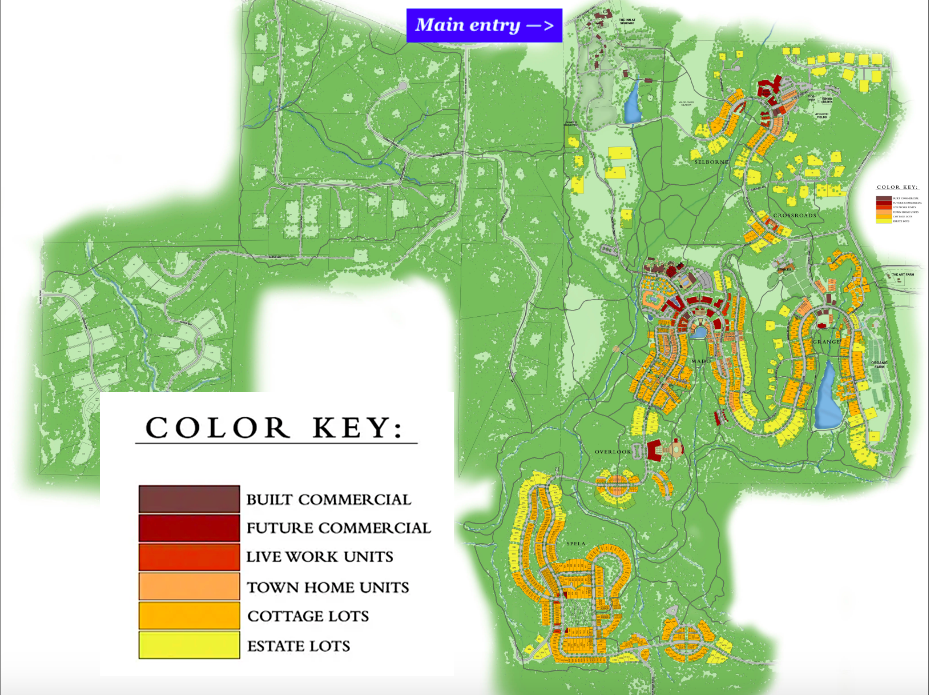

The full scope of Serenbe's land. This tour begins at Spela—with plots shown in orange and yellow, at bottom—and works up to The Inn and animal village at the main entry. Courtesy of Serenbe

The full scope of Serenbe's land. This tour begins at Spela—with plots shown in orange and yellow, at bottom—and works up to The Inn and animal village at the main entry. Courtesy of Serenbe

…

BIG picture, Serenbe’s footprint is 2,000 acres. That's about 10 Piedmont Parks, stitched together.

Of those, about 250 acres have been “disturbed” at this point, as Nygren puts it. But it’s written in stone, as part of the community’s legal structure, that 70 percent of the land will remain preserved in perpetuity. Which, as we’ll see, is arguably as much of the allure as proximity to the world’s busiest aviation hub. (Fun fact: Nygren says Serenbe accounts for 65 percent of the tax base in Chattahoochee Hills, allowing the city to hire 26 police officers, a full-time public works staff to maintain roads, and a full-time fire department. “When it was just unincorporated Fulton County,” he notes, “the taxes couldn’t support the area. If your house caught fire, it was going to burn down.”)

On the tour, our golf cart passes a shipping container that’s doubling as a makeshift post office at Spela, the latest Serenbe hamlet to start taking shape. Nygren points to handblown glass leaves that adorn new streetlights and whips blueprints out of a secret compartment.

From this hilltop, some 400 homes will eventually be built in Spela, with a grand staircase leading from the main street to a 4-acre park surrounded by Victorian-style homes. A high point, literally, will be a four-story mixed-use building at one corner of the park, with a coffeeshop at the base and cocktail lounge with rooftop seating on the top floors.

“You’ll be able to see everything,” Nygren says.

Moving on, toward more established Serenbe enclaves, we find the Victorian-inspired Overlook hamlet. Like all smaller, connecting neighborhoods, it’s painted pure white, for a unique contrast to its wooded surroundings and also a nod to late-1800s housing.

“Pigmented paint was very expensive back then,” says Nygren, “so they all tended to be unpainted or painted white.”

Overlook's distinctive color and design scheme. The first phase is shown here. Josh Green/Urbanize Atlanta

Overlook's distinctive color and design scheme. The first phase is shown here. Josh Green/Urbanize Atlanta

In terms of location, density, and buzz, the 400-home hamlet and commercial center Mado has emerged as Serenbe’s heart. It counts apartments above retail—and one storefront after the next that’s recently sprung to life.

Offerings include casual, clean-food eatery Halsa, the first OTP outpost of Soberish, Bamboo juice, Nigels Bananas treats, medical offices, a coffeeshop, a dentist, a physical therapist, and the Zen-inducing Spa at Serenbe (ask for masseuse Jennifer and thank us later).

“These businesses have all moved in in the past year—really amazing,” notes Olsen.

As we round a corner, to a sprawling communal area with a fire pit and one of many Serenbe playgrounds, with high banks of housing etched into the hills, Nygren bursts: “Look at this—there’s a totally new city!”

Indeed. With 17 units to each acre, Mado’s residential sections are relatively dense. Another grand staircase with 220 steps links the highest street, Lupo Loop, down to a lake that’s 32-feet deep and speckled with koi fish. The lake provides geothermal heating and cooling to all surrounding, Stockholm-inspired townhouses and a main commercial building nearby. Construction is beginning on a lakeside amphitheater, and on the flipside of a pathway, protected wetlands span off toward the setting sun.

“They think people don’t want to live in density, but they do,” says Nygren. “As long as you have a mixture with nature.”

We pop into a new modern house by custom homebuilder Vincent Longo overlooking Mado—priced at a mere $3.5 million. “This is the coolest one for sale,” says Olsen, entering the 5,000-square-foot showplace.

Two budding architecture enthusiasts related to the author, along for the ride, plop into seats at the pool lounge area out back—and instantly agree with Olsen.

The 5,000-square-foot home's primary bathroom, while being inspected by a discerning critic. Josh Green/Urbanize Atlanta

The 5,000-square-foot home's primary bathroom, while being inspected by a discerning critic. Josh Green/Urbanize Atlanta

We pass a permanent rock garden and come upon the well-known, short-term rental that is the Serenbe flatiron house. It was designed, Nygren notes, to work in concert with a white modern farmhouse across the street, forming a contrasting entry point to this section of the neighborhood.

“Look at all the rooftops, how it all glides down—this is specific,” says Nygren, waxing philosophic. “We designed how high every house could be and where it sits on the curve. If you’re not thinking about it, you don’t realize it, but you feel it. It’s very natural and organic. We really studied the difference between a development and towns that have been built over centuries.”

What wasn’t intentional—but just might be the tour highlight for a 10-year-old passenger— comes into view atop another hill. When constructing nearby houses, builders found themselves with tons of top soil but nowhere to put it. “I told them to just keep piling it here, and I’d figure something out,” says Nygren. The idea: a permanent, hilltop, in-ground trampoline with views over what’s come to be known as Sunset Point—with horse pastures, forests, and the new town school beyond.

The in-ground trampoline (one of several across Serenbe) at what's fittingly called Sunset Point. Josh Green/Urbanize Atlanta

The in-ground trampoline (one of several across Serenbe) at what's fittingly called Sunset Point. Josh Green/Urbanize Atlanta

Speaking of the school, Serenbe outgrew its former educational digs and opened the first phase of the Terra School in 2023, a biophilic facility powered by geothermal and topped with solar arrays. Its 230 students range from six weeks old to high school seniors, with yearly tuition for elementary and up in the $15,000 range, though scholarships are available.

“We have a third and fourth building that will be built as the student population grows,” says Olsen. “It’s pretty much full to sixth or seventh grade now.”

The Terra School, with low windows for little pupils at left, and higher grades at right. Josh Green/Urbanize Atlanta

The Terra School, with low windows for little pupils at left, and higher grades at right. Josh Green/Urbanize Atlanta

Directly across the street from the school, over a crosswalk, is the 7-acre woods where a wellness campus and aging-in-place housing is scheduled to break ground in a couple of months, Nygren says. Plans call for 48 cottages and 47 apartments atop retail as part of a $298-million growth spurt that’s scored financial backing from The Development Authority of Fulton County.

Also next to the school, the communal, membership-based Serenbe pool was installed about six years ago, with a heated pool swimmers use all year—and no shortage of sprightly pink architecture.

Heading toward Grange, an older hamlet next to the 25-acre organic farm, we pass the oft-photographed horse stables, more traditional streetlights, a five-story apartment complex designed to echo an 1800s brick cotton mill, and blueberry bushes at every crosswalk. (Another fun fact: 70 percent of Serenbe landscaping is edible.)

In the shadow of two large homes—a juxtaposition of clean-lined modernity and Inman Park-style traditionalism—Nygren explains his belief that variety isn’t necessarily negative.

“This just shows what you can do as long as you focus on massing and placement,” he says of the homes. “Look at the Victorian next to a brutalist contemporary—it all works.”

After Grange, we encountered another small, white-painted connecting neighborhood, fittingly called Crossroads, with a bike shop and new dog groomer.

The taller mixed-use structures were built with modular construction—a cutting-edge technique just before the recession.

The final hamlet, the modern-traditional mishmash Selborne, is what might come to mind when many Atlantans think of Serenbe. It’s the original street, where Nygren lives in a large townhome, and where I’ll enjoy two superb meals: Saturday dinner at swanky Austin’s (where even the cabbage dish is a work of art) and the hands-down best huevos rancheros (pilled with chicken and sweet potato hash on corn tostadas) to ever pass these lips at The Hill, a longstanding Selborne restaurant.

At the same brunch, it dawns on us that Serenbe isn’t the white-bread Mayberry situation outsiders could expect; it might be prohibitively pricey in many regards, but it’s proudly non-gated, and there’s real diversity beyond people’s accents.

Finishing the tour, we wind around wildflower meadows, the forest with a hidden labyrinth, another lake, the pasture where a gastro-anatomically talented horse called Dolly Farton grazes, and we come to The Inn at Serenbe, the farm and animal village where this all began. It’s the one place that hasn’t really changed.

Nygren takes pride in advances Serenbe has made in biophilic design, arts, and city-adjacent agriculture on this slice of Georgia hill country. Nonetheless, he says Serenbe’s relative obscurity in metro Atlanta is due, in part, to a south-of-Interstate-20 bias that hasn’t faded.

“Someone said we are what Aspen was years ago, as far as thought leadership, and instead of ski slopes, we have that airport that connects you anywhere,” says Nygren. “There’s one thing that people can’t buy no matter how much money they have—and that’s time.”

…

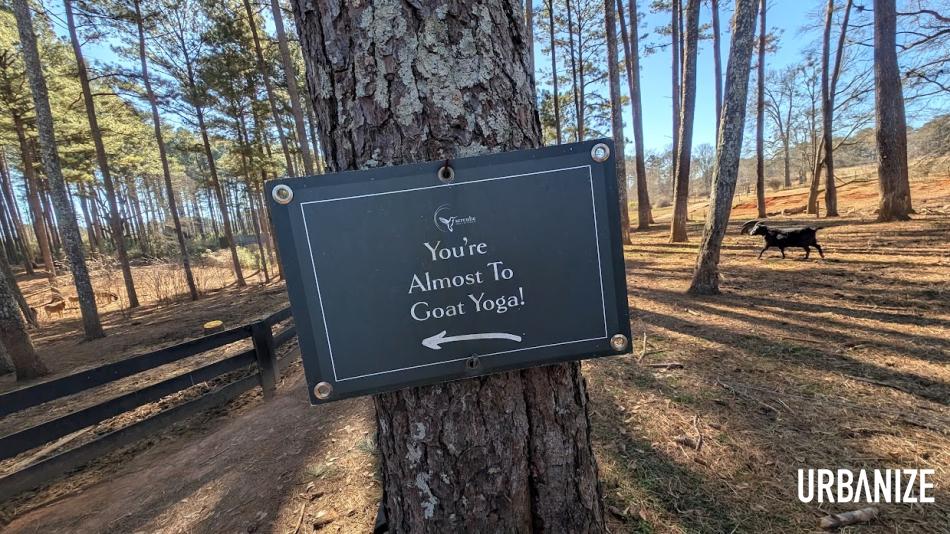

EVEN devout city folk must concede there’s something soothing about watching goats frolic from bed. Or setting out on a sunny day across a wooded trail network that now stretches for more than 22 miles, all of it open to dogs and bikes. “It’s never complete,” says Nygren, “and we’re constantly adding.”

Using those trails, we found out the good way it’s easy to walk a mile from a poké-bowl lunch and spa treatment back to the farm, around villages, all while being alone in quiet woods. The entire town is linked together by forested pathways.

The stay of less than 48 hours felt like a week, in the best way. The thrill of exploration—like those starry, country skies at night—puts the mind in a good place. Stresses melt off.

What's harder to shake, as we learned while packing up, heading back to the city: The urge to reach for the cellphone and call police.

That gunfire in the rural distance is totally legal—and just part of life out here.

In the gallery above, find more photos showing various aspects of Serenbe's 2,000 ares.

...

Follow us on social media:

Twitter / Facebook/and now: Instagram

• Special report: 24 hours at Trilith, Atlanta's country Hollywood (Urbanize Atlanta)