As commercial real estate brokers, Michael Palazzone and Tim Head have been part of deals involving interesting Atlanta properties, representing the sellers of downtown’s Odd Fellows Building as one example. But more recently, they’ve itched to buy land and create their own residential developments, helping fill the city’s housing void with denser options such as townhomes and making a buck in the process.

Early last year, the two heads of Lee & Associates Commercial Real Estate Services found what seemed like an opportune place to start: a .9-acre corner property at 2535 Glenwood Avenue in East Lake. Listed for $650,000, the lot is home to a vacant single-family house with a garage workshop behind it—owned by someone in California—that Head describes as an “old and beat… rat trap” with a squatter problem.

But beyond the lot’s size, the location was enticing. It overlooks the clubhouse and manicured greens of East Lake Golf Club, with a MARTA bus route running just outside of what, as Head and Palazzone envisioned it, would be the front doors of future townhomes. “We just felt like it was an underutilized piece of land,” says Palazzone, the firm’s director, “and a good location to do what we’re trying to do.”

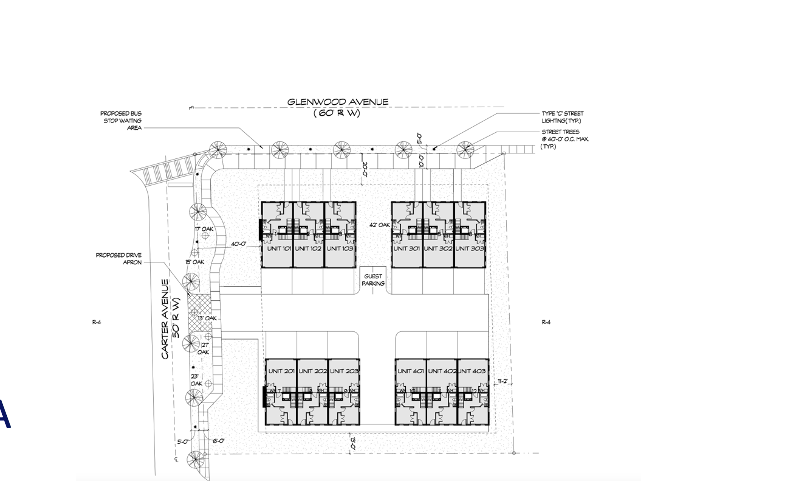

The would-be developers met with Pimsler–Hoss Architects and cooked up plans for 12 townhomes on the corner, with hopes of pricing them from about $500,000. They began a series of communal meetings, revisions, and compromise. But a year and ½ later, Head and Palazzone feel their vision for “Glenwood Homes” has been unfairly torpedoed by a small but vocal group of adjacent homeowners resistant to change.

“It doesn’t make any sense,” says Head, a principal. “All the people in the city are screaming for housing—we’re trying to provide housing. We’ve been so wronged.”

The existing vacant house at the .9-acre corner site at 2535 Glenwood Ave. Josh Green/Urbanize Atlanta

The existing vacant house at the .9-acre corner site at 2535 Glenwood Ave. Josh Green/Urbanize Atlanta

The East Lake situation marks the latest case of relatively dense intown housing being called into question by neighbors who fear aspects such as added traffic and noise. Developers on Edgewood’s Whitefoord Avenue, as one example, were forced by neighborhood pushback to scrap plans last year for up to 48 “missing middle” housing units in vintage-style buildings also near MARTA transit. The replacement for those plans—large modern duplex units priced at $950,000 and up—are now coming to market instead.

The thorn in Head and Palazzone’s side, so to speak, is the adjacent master-planned neighborhood of Olmsted, which would share a city-street entrance with the Glenwood Homes site. Beyond its manicured entry sign, Olmstead is a leafy enclave of 91 housing units, including large stately residences in a variety of styles and 27 more tightly packed townhomes. Attempts to reach Olmsted representatives for comment this week were not successful; the community’s de facto spokesperson, John Marshall, said he would forward requests for an interview to the rest of the community, but no one had responded by press time.

Manicured entry to the 91-home Olmsted community near East Lake Golf Club. Josh Green/Urbanize Atlanta

Manicured entry to the 91-home Olmsted community near East Lake Golf Club. Josh Green/Urbanize Atlanta

The initial proposal included 12 townhomes with access on Carter Avenue, the main entry to Olmsted. After hearing concerns in neighborhood meetings, Head and Palazzone agreed to move the entry to busier Glenwood Avenue, a main East Lake thoroughfare, and reduce the unit count to 10.

Documents provided to Urbanize Atlanta show those plans received about 85 percent approval last year during votes taken during both East Lake Neighborhood Community Association and NPU-O meetings.

For the next step, Head and Palazzone took their plans to the City of Atlanta’s Zoning Review Board, along with a letter of recommendation from city councilmember Liliana Bakhtiari. The ZRB board recommended the developers work with staff on a few changes to the plans. In that meeting, according to Palazzone, Olmsted neighborhood reps heard commentary that emboldened them to believe they could push to have the plans changed again to a lower density.

“They believed they had leverage,” says Palazzone. “They turned south on their approval, and said we’re not going to support you anymore before the next ZRB [meeting], and we want you to do eight units.”

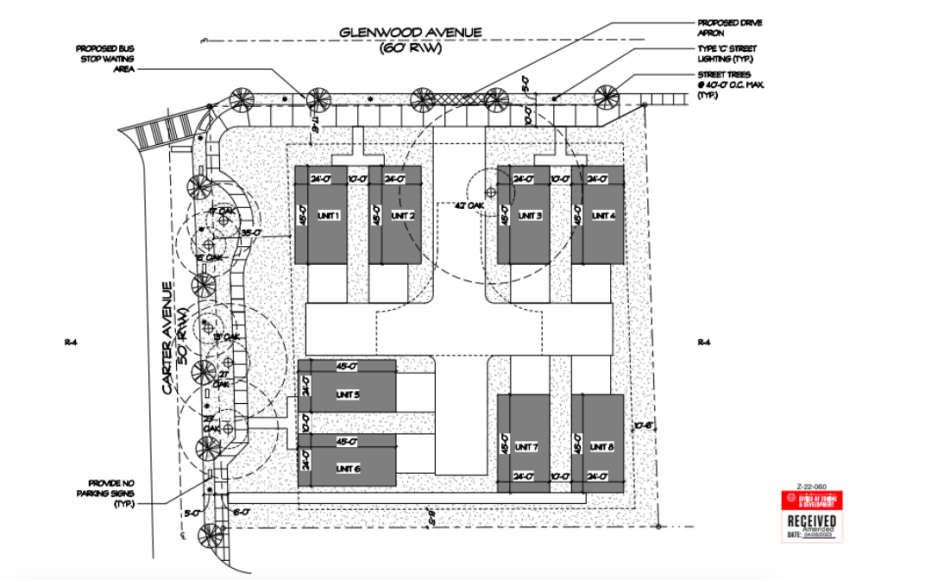

After back and forth with city staff, and trying to gain approval for a plan with nine units, Head and Palazzone enlisted architects to draw up a scheme with eight standalone houses and started the process again of trying to gain approval in February. But according to the developers, a subset of the neighborhood wanted even fewer units, and they packed ELNCA and NPU-O meetings this year with naysayers, who voted against approval in landslides. Inquiries to ELNCA and Bakhtiari’s office this week were not returned.

Nonetheless, Head and Palazzone’s request to rezone the Glenwood Avenue corner to single-family PDH, or planned housing, received unanimous approval in May from both the ZRB and its Zoning Review staff.

Initial plans for 12 townhomes that would have been accessed via a street shared with the Olmsted community. Lee & Associates Commercial Real Estate Services; designs, Pimsler – Hoss Architects

Initial plans for 12 townhomes that would have been accessed via a street shared with the Olmsted community. Lee & Associates Commercial Real Estate Services; designs, Pimsler – Hoss Architects

The revised plan for eight standalone houses filed with the city in August.Lee & Associates Commercial Real Estate Services

The revised plan for eight standalone houses filed with the city in August.Lee & Associates Commercial Real Estate Services

Only one more step, a Zoning Committee vote, remained before the project’s zoning would go before the city council for a vote, a prerequisite before building permit applications are allowed. But just before that meeting, according to Palazzone, Bakhtiari’s office informed the developers the Zoning Committee planned to table the matter until further notice.

More than two months later, the developers feel the dissent of some Olmsted neighbors is to blame for keeping their project in “purgatory” and “held hostage” at the city level. Being struck down in Zoning Committee would essentially be a death sentence for the current plans, Palazzone says.

“If the city wants more housing, it can’t only come from big developments,” Palazzone says. “We’re doing everything we can to work with the committee, but it’s been a very challenging process.”

Opponents generally feel the site is more appropriate for three to four single-family homes, or at most six, though some neighbors during meetings have called townhomes an appropriate use.

The days of being able to offer homes in $500,000s has passed, according to Head and Palazzone.

The eight freestanding houses on the boards now would each span about 2,150 square feet, likely with three bedrooms and starting price tags in the $750,000 to $800,000 range. The developers' purchase of the property is contingent on zoning approval. No additional hearings or meetings for moving the process forward have been set.

“If we had to do six [homes], we couldn’t do it. Eight is the only way we’re going to walk away with very little money,” says Head. “They’ve driven us to not providing a more affordable piece of housing. It is ironic.”

Another cost consideration is the “substantial architectural monies” the developers have committed to changing plans four or five times, says Head. Nonetheless, as things stand now, he says walking away is not an option.

“With the Zoning Review Board’s unanimous approval, we’re in this to win, man,” says Head. “We’re not going to get rich—it’s not like some money grab. At this point, we’re making very little money. But we’ve been dealt with so poorly, it’s almost become a challenge.”

...

Follow us on social media:

• East Lake news, discussion (Urbanize Atlanta)