Impromptu volleyball matches, sunbathing near the water, and diverse groups of families biking together are scenes typically reminiscent of, say, Venice Beach or Miami. However, tucked away in the heart of Atlanta’s Westside, Shirley Clarke Franklin Park, formerly known as Westside Park, offers locals an alluringly lush getaway much closer to home.

Heralded as Atlanta’s biggest greenspace, the nearly 300-acre property has had large shoes to fill in the tapestry of the city’s improving parks system since the completion of its first phase in 2021. As the only truly large public greenspace in Northwest Atlanta, expectations around Shirley Clarke Franklin Park have been high since its inception for both the community and the city.

With the park nearing its fourth anniversary—and almost 20 years after its conceptualization—the question remains: Has Shirley Clarke Franklin Park lived up to its potential?

And if not, what needs to change?

A functional greenspace’s origins

For Atlanta newcomers, a quick history: Excitement for the park, even in theory, ratcheted up after the city’s acquisition of Bellwood Quarry during the tenure of then-Mayor Shirley Clarke Franklin in 2006. The quarry within Westside Park would become a sparkling reservoir that holds more than 2 billion gallons of emergency drinking water, boosting Atlanta’s water supply from three days to more than a month. “This was a big leap, [and it] puts us at the helm of [being] a more resilient city in case of emergencies and being more prepared from a sustainability standpoint,” says Lynette Reid, Atlanta Beltline’s vice president of planning, engagement, and arts and culture.

Those city-led sustainability efforts would spawn the creation of Westside Park as a much-needed greenspace in an area that trailed other parts of town. “One of the highest priorities in the Beltline plan was the Quarry Park,” Penny McPhee, previous president of the Arthur M. Blank Family Foundation, said in a 2019 Saporta Report article. “It would be a community park and a regional park, and it would provide the same kind of amenities on the Westside that Piedmont Park provides on the Eastside.”

The Blank Foundation, a philanthropic organization started by Home Depot cofounder Arthur Blank, was pivotal to the park’s development, providing a $17.5 million grant, the largest gift to the Beltline in 2019.

Aided by a massive drilling machine nicknamed “Driller Mike,” construction to fill the quarry with water diverted from the Chattahoochee River began in 2015 and finished in 2020—roughly a year before the completion of Shirley Clarke Franklin Park.

“It was very exciting that Westside Park was going to be a thing in NPU-G,” recalls Torrey Sumlin, the Neighborhood Planning Unit’s current chair and a Westside resident since 1989. “It was very needed.”

Shirley Clarke Franklin Park is situated in both NPU-G and NPU-J, including historically Black neighborhoods such as Carver Hills, Grove Park, and Rockdale. “One of the parks that we had—or still have—is English Park,” says Sumlin “That park was antiquated with old amenities [until recent upgrades]. So NPU-G never really had anything where people could go walk a trail and sit out or just enjoy being out on the lawn.”

Shirley Clarke Franklin Park has bolstered the general accessibility to recreational space in the area alongside another key change: construction of the Beltline’s Westside Trail and the Westside Beltline Connector, the latter a paved multi-use spoke extending out from downtown.

Access to greenspaces such as the park and Westside Trail are known determinants of positive health outcomes. According to a 2024 Trust for Public Land report, cities with higher parks and greenspace accessibility tend to have lower rates of reported poor mental health and physical inactivity levels. TPL also highlighted the park-space inequality in American cities where people of color “had access to an average of 43 percent less park acreage than predominantly white neighborhoods.” A similar trend is seen in low-income areas as well, per TPL’s analysis.

The establishment of Shirley Clarke Franklin Park has worked to address disparities in local neighborhoods—and neighbors have excitedly adapted. “Working with the Grove Park Neighborhood Association, we’re actually starting a neighbor walk that will happen the first Saturday of every month,” says Lauren Smith, Grove Park Association president. “It’s our way of getting more neighbors out to the park, so that they can see how beautiful it is. [We want to] encourage more movement and also create something that will connect the neighbors a little more often.”

Westside team efforts

Justin Cutler, Atlanta’s Department of Parks and Recreation commissioner, says a significant contributor to the park’s success is a collaborative “group project” mindset that begins with Mayor Andre Dickens’ office and trickles down.

“We’re working with the Beltline Partnership, Department of Watershed, [and] Department of Parks and Recreation to create a beautiful greenspace,” notes Cutler. “We’re working with the Grove Park neighbors, West Highlands [residential community] and that whole area as it changes and evolves.”

Currently, the most significant change for the area, according to residents interviewed by Urbanize Atlanta, has been adjusting to the sheer number of events now happening nearby. According to Smith, “the events that have been coming through have been good for the community. Just bringing more people to this side of town.” Sumlin echoes that sentiment, for the most part. “We get a lot of events in the park,” says Sumlin. “Some constituents in NPU-G might even say it’s been overused. Because it’s a new park in the city, people throw events that they normally have at Piedmont Park over [here].”

According to the Department of Parks and Recreation, 38 permitted events occurred at Shirley Clark Franklin Park in 2024. The number has ramped up with 33 events already occurring in the park as of June, meaning the frequency of events has almost doubled over the past year.

As the park has drawn attention to the area, the inevitable conversation around housing affordability has started to heat up.

Currently, city and Beltline officials are working together to ensure affordable housing measures put in place before the park’s development live up to promises, says Reid. “Sometimes, with public infrastructure, you feel the pressure of affordability after it,” Reid says, “so this was a way to get ahead of it.”

Within the multitude of affordable housing measures, the Westside Affordable Housing Overlay District is most notable. The overlay district sets a requirement for developers to maintain a certain amount of affordable units in new construction. In Westside’s case, it’s 15 percent of new units at 80 percent of the Area Median Income, or 10 percent at 60 percent AMI. “That’s just to build in some affordability,” notes Reid.

Beltline officials stress that they’ve used a multifaceted approach to ensure residents are able to remain in their homes, despite pressures usually faced after a popular greenspace is added to an area. Another example is the Atlanta Beltline Legacy Retention Program, in which residents are able to apply to have property taxes subsidized to 2019 rates to offset the typical rise stemming from new development. Currently, the Beltline has 250 homeowners from around the western and southern Beltline corridor in this program, with fundraising efforts underway to potentially expand the program.

Changes on horizon

Looking toward the future, as the Westside continues to pack on housing, the park’s amenities will be expanded in coming years, according to city leaders.

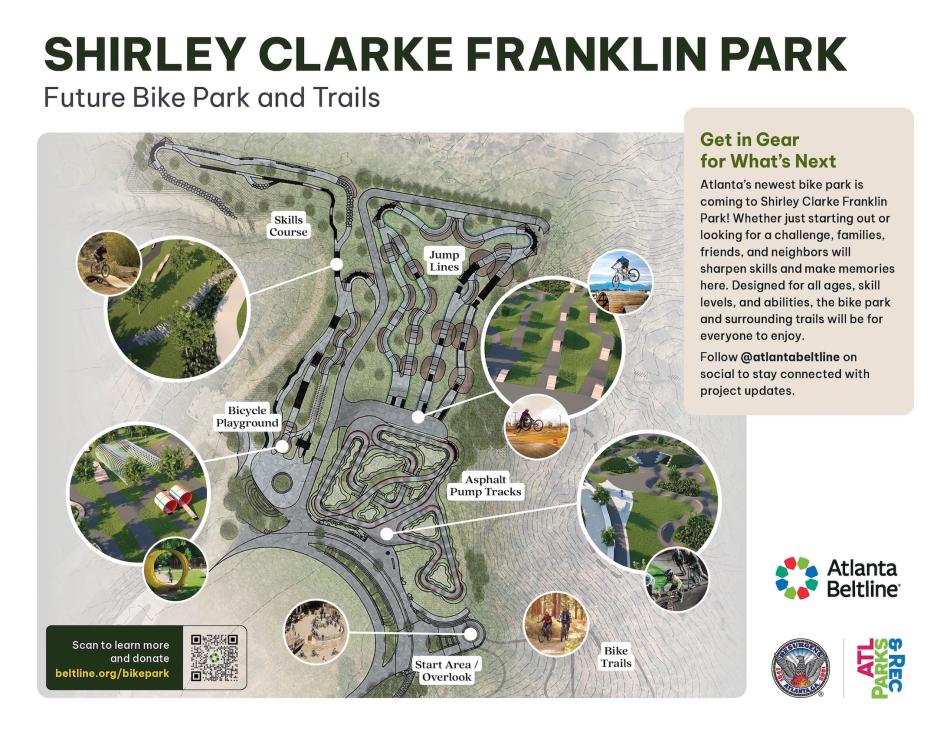

The Beltline announced the creation of a new bike park, thanks in part to an $8-million donation from the Chestnut Family Foundation, in 2024. Beltline Partnership officials are now in the midst of fundraising to reach a $15-million goal to get the project moving.

Plans call for 2.25 miles of all-skill-levels trails, inclusive mountain bike trails, a bike playground for kids and beginners, and a dual-purpose starter area that also functions as a scenic overlook and gathering space. If all goes as planned, it will serve as a tourism magnet for passionate bike riders and a hub for local enthusiasts and those wanting to acquire a new skill.

Construction of the bike park is planned to begin at the end of 2025, according to Beltline officials.

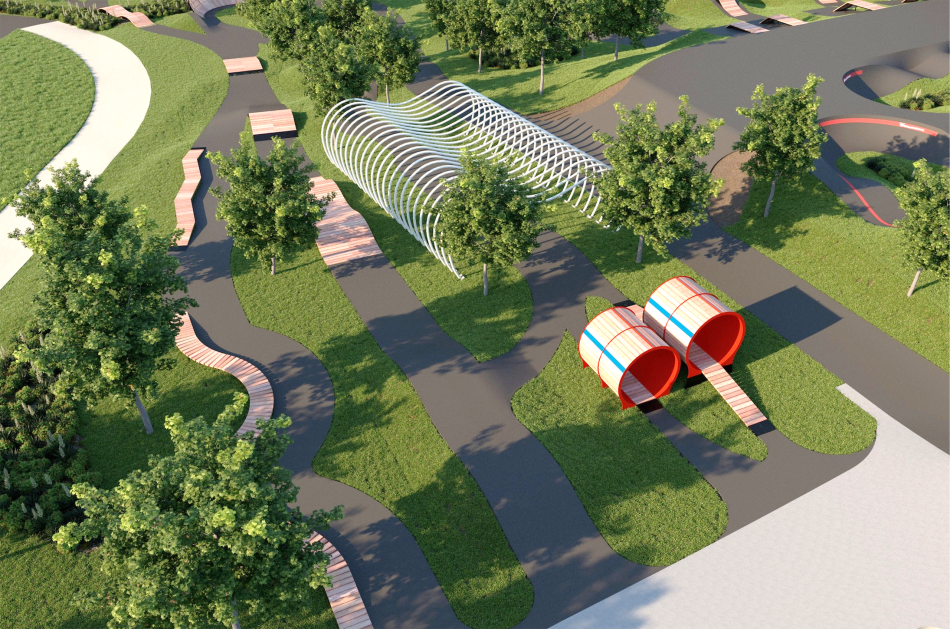

Challenging course features and an architectural section that echoes the park's existing "ribcage" gateway. Courtesy of Atlanta Beltline Inc.

Challenging course features and an architectural section that echoes the park's existing "ribcage" gateway. Courtesy of Atlanta Beltline Inc.

“A lot of people are excited, not only [about] the new biking trail, but they know they’ll have an opportunity to actually be able to walk on those trails as well,” says Sumlin, noting that neighbors are eager for bike trails that connect multiple NPUs in the region. “That’s something people have actually been excited about for a couple of years. They always thought the park should have walking trails that actually connected to something.”

Connectivity on broader scale would improve the standard of living in the region for years to come, says Sumlin.

Shirley Clarke Franklin Park, in summary, continues to be a work in progress—but also a group project that aims to address present-day needs of the local community and the city as a whole, while also honoring the past.

“It’s an interesting park in that sense,” says Cutler “You have this now older element being celebrated, and then we have the legacy of Franklin. You have the Rebirth of Atlanta, which is now there as an art sculpture after you enter the [artist-sculpture entry] Ribcage.

“The park really does an amazing job of honoring the past,” Culter continues, “[while] looking toward the future, and also connecting with the current needs and [the] emergent opportunity there with the water supply.”

...

Follow us on social media:

Twitter / Facebook/and now: Instagram

• Grove Park news, discussion (Urbanize Atlanta)