Editor’s note: As Georgia continues to swell with new residents, all forms of development, and pressures and problems inherent in urban growth, metro Atlanta attorney Matthew Wages Johnson, like many, has taken a keen interest in urbanization. Below, Johnson shares observations on how Milledgeville—a former Georgia state capital, college town, and historic destination that remains under-the-radar for many Atlantans—could shine by limiting car access and embracing people-friendly infrastructure.

...

Before Atlanta, there was Milledgeville.

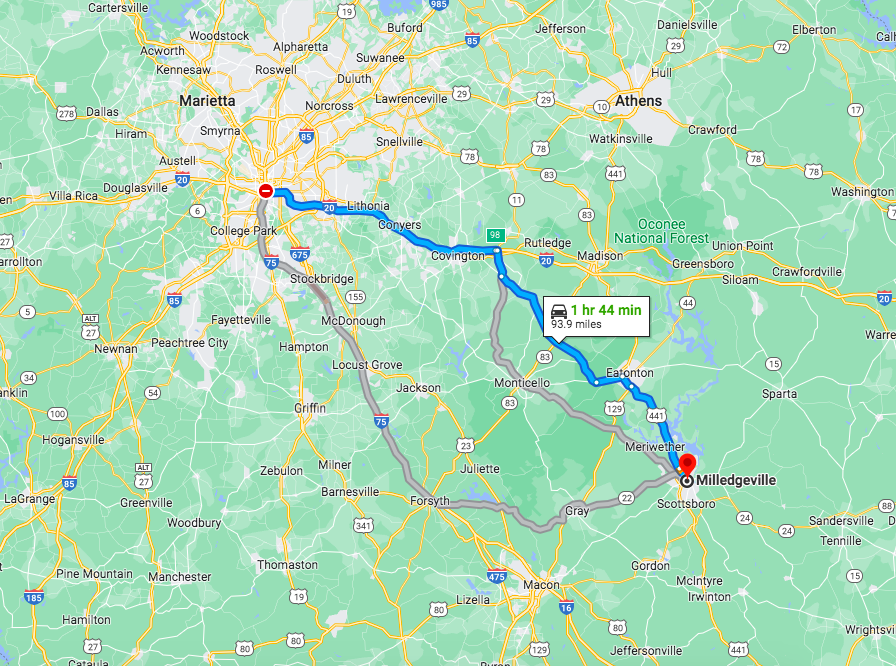

Located about 90 miles from Atlanta in Central Georgia, Milledgeville served as the Peach State’s capital from 1804 until 1868, and the Old State Capitol and Old Governor’s Mansion are reminders of the city’s important former role today.

That could be news to Atlanta newcomers. But similarities between the two cities—one could argue college towns, both—don’t end there.

Milledgeville’s growth has made it the home of Georgia College & State University, a four-year institution with more than 6,800 students located across the street from downtown. Milledgeville boasts so much charm, in fact, Budget Travel named it one of the 10 Coolest Small Towns in America in 2019.

But Milledgeville could become even cooler and more visitor-friendly by pedestrianizing and densifying its downtown and by adding high-quality bicycle infrastructure. (Sound familiar, Atlanta?)

Here’s my 2 cents. It’s not too complicated.

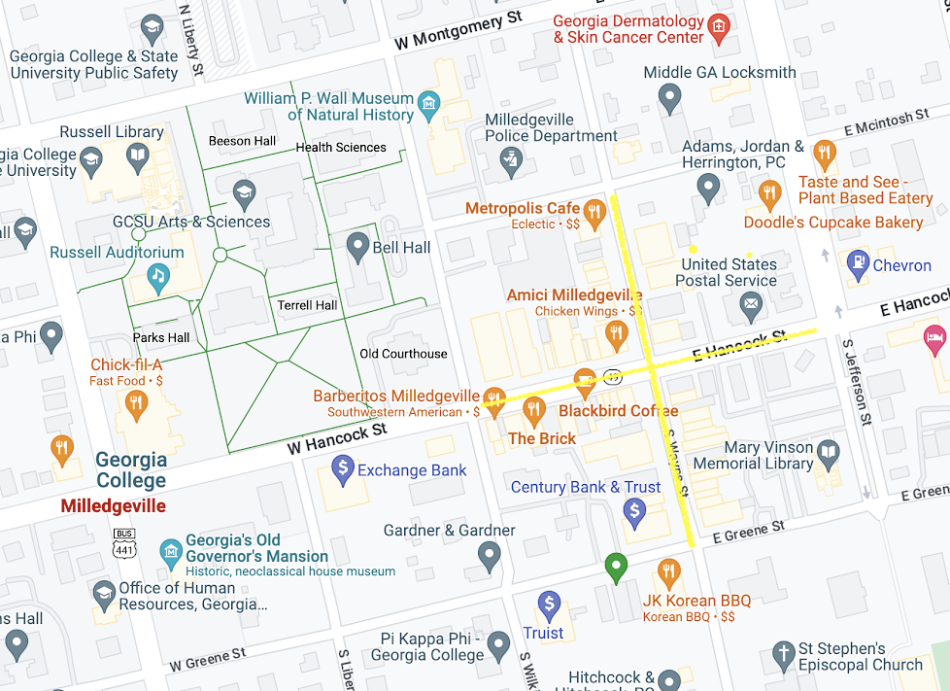

Start by pedestrianizing the heart of downtown Milledgeville on Hancock Street, between Wilkinson and Jefferson streets, as well as on Wayne Street between McIntosh and Greene streets. Replace the asphalt with stone paving, add more street trees, and remove the street signs and traffic lights. A good rule is that if given a choice between a car-filled intersection that is deadly to humans or an intersection with a fountain around which humans can enjoy life, then planners should choose the latter. So add a fountain at the intersection of Hancock and Wayne.

Creating inviting spaces really can be that simple.

Pedestrianization would open up downtown to maximal living, because when cars are prohibited in a downtown area, human activity fills the void. Downtown would be Milledgeville’s living room, and guests would have open access to benches, tables, and wi-fi, as well as public restrooms that are funded by small, optional charges. They could enjoy a quiet afternoon free of noise pollution and exhaust fumes from cars, and they could cross the street without the possibility of being crushed by an automobile. Outdoor dining, concerts, festivals, and large screens for movies and sporting events are just a few changes that would enhance life in Milledgeville.

Large parking lots in the downtown of a college town are signs of planning failures, and downtown Milledgeville is littered with them. Unfortunately.

With less demand for cars and more demand for living and working in an improved downtown, builders could turn those parking lots into residences and small businesses. Thinking long-term is key, and new buildings should be high-quality structures in enduring architectural styles meant to last for generations.

Milledgeville should foster the easiest way for students and residents to access the city, which is through bicycle infrastructure that has wide, protected bike lanes, not just strips of paint on roads. The message to drivers through street design should be that pedestrians and bicyclists have priority, and when walking, biking, and driving conflict, the onus for safety should be on the person who controls the multi-ton box of steel.

Unlike Atlanta, Milledgeville is relatively flat and full of energetic young people who would jump at the opportunity to have easy access to their city via bikes.

Intersection of Hancock and Wayne streets, about three blocks from the college campus. Matthew Wages Johnson

Intersection of Hancock and Wayne streets, about three blocks from the college campus. Matthew Wages Johnson

Americans are so blinded by car-dependency that turning the most central part of a dense college town into a walkable, bicycle-friendly area would be controversial to business owners, but downtown Milledgeville has the small shops and restaurants that would benefit dramatically from increased foot traffic. Businesses need customers, and the best means of getting customers downtown is by making downtown accessible by bikes.

Quality bicycle infrastructure would transform life in Milledgeville, but inter-city rail would be the ultimate game-changer, because people could commute to other cities in peace, productivity, and comfort. If America ever gets its act together and rebuilds the passenger rail system that it destroyed last century, then a train trip to Atlanta at an average speed of 150 miles per hour with a connection in Macon would take about 45 minutes. And, given the rise of working remotely, that trip might have to be made only a few times per month, but it would allow for the face-to-face contact that could make employment in Atlanta possible.

In my experience, I’ve learned many Americans are not opposed to growth, per se, but they are opposed to standard American growth, with its destruction of nature, tax increases for expensive infrastructure, and ugly buildings in seas of asphalt. The result is that Americans spend even more time in even worse traffic while driving even greater distances from strip mall to strip mall—strip malls that in a few decades might be empty economic deadweights.

Pedestrianizing and densifying downtown Milledgeville, while adding bike infrastructure, would be the polar opposite of standard American growth.

As I recently walked on a sidewalk in Milledgeville, I overheard a mother exclaim to her daughter, an incoming Georgia College student, “You can walk to town!” Her comment was unintentionally insightful, as both the mother and daughter probably had spent their entire lives knowing nothing other than car dependency, so it must be strange to do even simple tasks without a car.

Walking to town is a nice improvement, but the goal for Milledgeville’s planners should be to make the city so enticing that the daughter never wants to leave.

Bit by bit, and street by street, America’s historic small cities can be reclaimed from car dominance and turned into charming, fulfilling, economically productive places, and downtown Milledgeville would be a great place for Georgia’s efforts to begin.

Targeting college towns ultimately can de-program young adults from the orthodoxy that a car should be necessary for functioning in society and can show them that it is not just possible but desirable to live a car-lite or even car-free life. Even if Milledgeville no longer is Georgia’s political capital, it should become Georgia’s capital for making its historic cities livable and lovable.

Matthew Wages Johnson is a UGA alumnus, a veteran, and an attorney who practices in the Atlanta area. He shared similar thoughts on making downtown Athens more people-friendly in February.

...

Follow us on social media:

• More Letters to the Editor from around Atlanta (Urbanize Atlanta)