Editor’s note: As Georgia continues to swell with new residents, all forms of development, and so many pressures and problems inherent in urban growth today, metro Atlanta attorney Matthew Wages Johnson, like many, has taken a keen interest in urbanization. Below, Johnson shares observations on how Athens—a jewel of downtown walkability that’s near and dear to his heart—could shine with changes limiting car access. Providing, perhaps, a blueprint for Atlanta.

For the uninitiated: Nestled 70 miles east of Atlanta, in the hills of Georgia’s northland, is Athens, famously home to the University of Georgia. Atlanta would not be the city it is without UGA, the state’s flagship public institution of higher learning and the alma mater of many people who drive Atlanta’s progress. Having a better Athens means having a better UGA, and having a better UGA means having a better Atlanta.

The Georgia General Assembly chartered UGA in 1785, and a hilltop above Cedar Shoals and the Oconee River was chosen in 1801 as the site for the university. The area was named for the ancient Greek city of Athens, and the town was incorporated in 1806. By 1841 railways began to link Athens to other cities, and Athens today is the home of a university of more than 40,000 students, the roots of music groups like R.E.M. and the B-52s, and the back-to-back national champion Georgia Bulldogs football team.

Downtown Athens’ proximity to a large university spared it from the wrecking balls that destroyed so many beautiful, historic downtowns in America during the middle of the 20th century. It’s still packed with great architecture, shopping, restaurants, and entertainment. Athens routinely is ranked as one of the best college towns in America, but it should become even better. How? By pedestrianizing much of its downtown and devoting its streets to people and living—not automobiles and driving.

Though Athens has made progress towards pedestrianization on College Avenue, the city should:

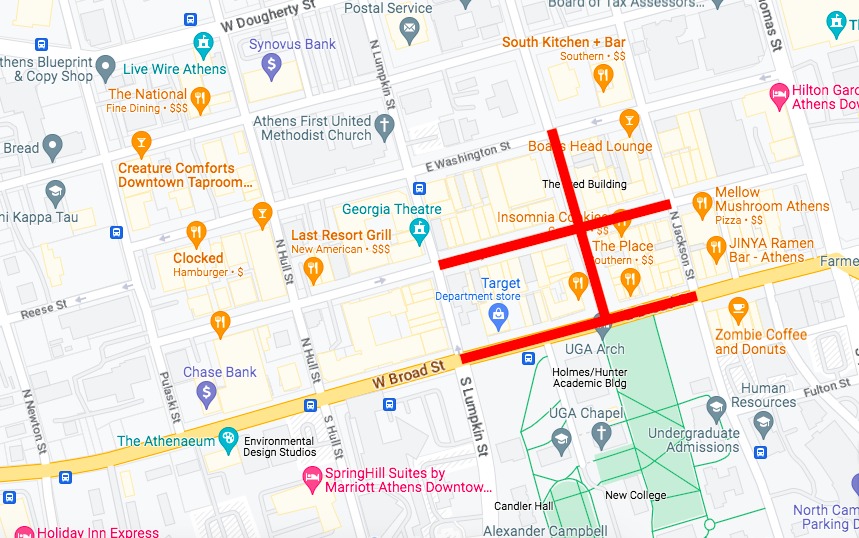

Pedestrianize Broad Street between Lumpkin and Jackson streets; Clayton Street between Lumpkin and Jackson streets; and College Avenue between Broad and Washington streets.

Extent of the streets in question (in red), with UGA's iconic campus entry depicted at bottom right. Google Maps

Extent of the streets in question (in red), with UGA's iconic campus entry depicted at bottom right. Google Maps

Elsewhere, Athens should remove on-street parking on Broad Street between Jackson and Thomas streets, and on Clayton Street, also between Jackson and Thomas streets.

Pedestrianizing downtown Athens would be a case of small sacrifices for large gains. Drivers would lose access to sections of a few streets and about 190 public parking spaces for their private vehicles, but human activity downtown would explode. Simplicity and beauty would be key, with street trees, tables, chairs, benches, and water fountains, as well as public restrooms funded by small, optional fees. The sidewalks and streets would be equal in height, erasing the distinction between them. And, since asphalt is ugly and hostile, the streets ideally would have stone paving, which is beautiful, inviting, and durable.

Ironic as it may sound, pedestrianization would also benefit drivers, because drivers are competitors with each other for road space and parking, and fewer drivers means fewer competitors. The more students who walk or use bicycles, the less of a headache that driving and parking downtown and on campus would be.

Drivers would benefit from parking predictability, because they’d know that no on-street parking in pedestrianized areas would be available. Instead of driving around and looking for desirable on-street parking, drivers would head immediately to parking decks, save time, and contribute less to traffic. In the longer term, decreased demand for parking could mean redeveloping parking lots into even more of the small businesses that help make downtown Athens so unique, and those businesses would benefit tremendously from pedestrianization.

Small businesses lack widespread name recognition and large advertising budgets, and they thrive in dense, walkable areas, where foot traffic builds the familiarity and credibility they need for profitability. For independent restaurants, coffee shops, and bars, their storefronts can be their best advertisements, and the more people who walk past, the more customers they’ll hypothetically have. UGA students become loyal to downtown’s small businesses in ways they’re not to chain establishments, and alumni are forever fond of the small businesses they patronized during their college years.

But this is key: Since pedestrianized downtowns are foreign to modern Americans, business owners would likely be apprehensive about prohibiting cars, so Athens should be as accommodating as possible.

Restaurants, coffee shops, and bars would have the right to use street space, increasing their usable square footage at no cost and creating opportunities for outdoor dining that don’t involve looking at a parking lot. Delivery trucks would have generous access to the pedestrianized areas, too.

Pedestrianization would also mean spaces for festivals, movies, and viewing football games on outdoor televisions, drawing even more customers to downtown. People, not cars, buy goods and services, and the best way for attracting people is by making downtown as attractive as possible. Downtown’s businesses would stand in even greater contrast to the sterile strip malls and drive-thrus that are both a product of and cause of car dependency, which forces people to have automobiles for functioning in society.

Car dependency psychologically disconnects a city from its residents and its residents from each other, and it makes the simple act of buying a cup of coffee prohibitively difficult. Thousands of students live within a two-mile radius of downtown, yet in order to buy a cup of coffee downtown, a student must get into a car, drive that car to downtown, undergo what could be a long search for parking, pay for parking, and then walk what could be a long distance to a coffee shop.

If Athens had wide, protected bike lanes—not the comically dangerous strips of road space that pass for American bike lanes—then a student who lives two miles from downtown could take an e-bike, arrive downtown in less than 10 minutes without breaking a sweat, park for free at a bike rack near a coffee shop, and generate the revenues that make that coffee shop successful. Bike lanes would make downtown accessible in radically new ways.

In short, build quality bicycle infrastructure in a dense college town, and students will use it to make the town even livelier.

Alumni might lack the vivacity of students, but they do have a deeper appreciation for how fleeting life is. Time is our most valuable resource, and burning it away in cars is time wasted. Car infrastructure crowds out human activity (see: Atlanta’s downtown Connector). Every square meter in downtown Athens devoted to cars now is a square meter where a tree cannot grow, where old friends cannot hug, and where reading a book cannot happen. Cars are advantageous in certain contexts, but the freedom that comes with being chained to an automobile for doing even the most basic tasks has tremendous financial, psychological, and social costs.

Urbanists—advocates for humane cities—should think and act strategically, and college towns should be targets for spreading ideas that improve cities. Urbanists’ main disadvantage is that most Americans never have been exposed to walkable and bikeable cities, but urbanists’ main advantage is that once people do experience the everyday tranquility, joy, and fulfillment that those cities engender, there is no turning back.

College towns are full of young adults who are intelligent, social, and receptive to new ideas, and spending four years in places that have excellent urbanism would demonstrate that people should not have to study abroad in order to experience quality cities. During any given decade, perhaps 100,000 students cycle through UGA, and many will become policymakers and leaders in Georgia and beyond. UGA might have a higher concentration of metro Atlanta natives than metro Atlanta itself, and Atlanta and its suburbs, which are shining examples of how car dependency harms quality of life, could be prime beneficiaries of an improved Athens.

Pedestrianizing downtown Athens would mark the re-unification of UGA and Athens. Broad Street once again would connect, not separate, campus and city, and for the first time in several decades, a student could cross Broad Street without the danger of being crushed by a multi-ton box of steel. In a perfect world, Georgia could shift resources from cars, whose users nationwide annually receive hundreds of billions of tax dollars in subsidies through road construction and maintenance, to mass transportation, whose users pay for their use.

Athenians could take advantage of the economic opportunities that Atlanta offers, and they could avoid the nightmare of Atlanta traffic and instead have peaceful, predictable, productive commutes via rail. With the proper foresight, the Athens of 2040 could have a walkable downtown, streetcars, and inter-city rail service—all of which the Athens of 1920 had, right as the totalitarianism of the automobile began to wreck so much of American life.

Athens is a good city, but for a city to be great, its downtown streets must serve purposes greater than those of driving and storing cars. People will use as much of the streets in downtown Athens as policymakers allow, and policymakers should allow them to use far more. Pedestrianizing downtown for generations to come would be one of the easiest victories UGA and Athens ever witnessed. It is time, as Bulldogs football fans say, to finish the drill.

Matthew Wages Johnson is a UGA alumnus, a veteran, and an attorney who practices in the Atlanta area

...

Follow us on social media:

• Athens news, discussion (Urbanize Atlanta)