Shannon Powell is Avondale Estates’ assistant city manager today, but in the summer of 1991, she was an intern in the City of Atlanta’s planning department. One day, she slipped away from her office and stumbled into a spectacle in City Hall’s atrium she still vividly remembers: People buzzing around in business attire, a media frenzy, one grand proclamation after the next from a podium, and a presentation showing a big city getting significantly bigger. All the hullabaloo of a major groundbreaking, that is, but without a shovel in sight.

“I was just a young spectator,” Powell says today, “trying to figure out what all the excitement was about.”

The excitement, as the general public was also learning from that July 1991 press conference, was spurred by the most ambitious development proposal in the history of a city built—to this day—on big architectural ideas hitched to grandiose real estate plays.

The project was called GLG Park Plaza. Its creators had control of 11 blocks in Midtown, a vast urban palette ready for cranes and a full battalion of high-rises. The initial phase, the audience was told, would begin that fall. By the Centennial Olympic Games five years later, the project’s centerpiece—the vacant, crumbling Biltmore Hotel, a vestige of 1920s Atlanta—would be revived, with a grand park in front where embassies from around the world would congregate.

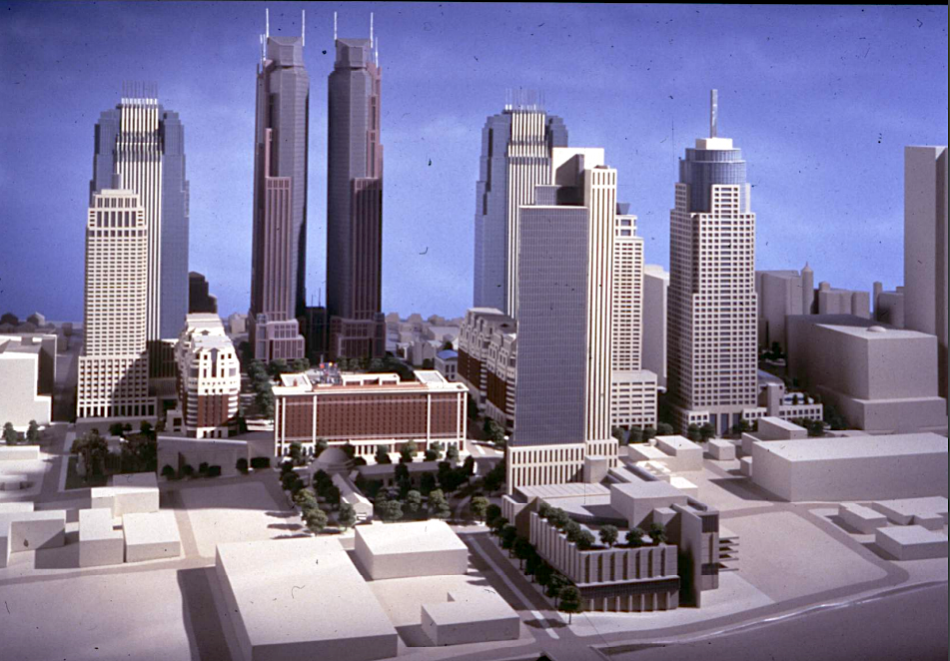

Looking south, toward downtown, with Atlanta's tallest building, Bank of America Plaza, depicted in the distance.Courtesy of Joe Rabun

Looking south, toward downtown, with Atlanta's tallest building, Bank of America Plaza, depicted in the distance.Courtesy of Joe Rabun

GLG Park Plaza wasn’t the only major development in the city’s beleaguered arts and theater district back then, but it was the strongest proof, as one research firm executive told the New York Times, that, “It’s just a matter of time before Midtown and downtown are considered one.” The scale made Colony Square and AmericasMart look like strip malls.

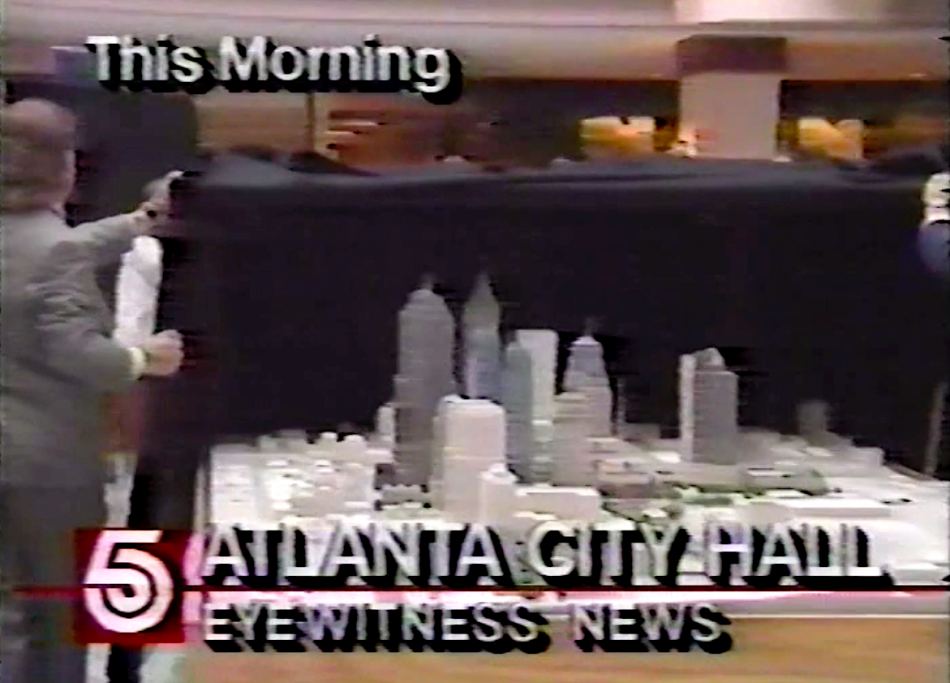

In broadcast news footage of the project’s unveiling, WAGA 5 anchor Jim Axel called it a “construction miracle,” and two former Atlanta mayors in the room were duly impressed. “I certainly think the fulfillment of it would be one of the major developments in the city’s history,” said Ivan Allen, in his drawl and Coke-bottle spectacles. Sam Massell, meanwhile, beamed: “Oh, it’s awesome. It’s tremendous, dramatic, exciting! I can’t use enough superlatives—it’s a very good thing for the city.”

When asked by a WAGA 5 reporter for his reaction upon first seeing this “thing,” Mayor Maynard Jackson leaned toward the camera, nodded, and said: “I was floored, I was amazed, I was bowled over! I couldn’t believe it. This is a city-altering kind of project. Nothing in America compares to it, with the exception possibly of Rockefeller Center.”

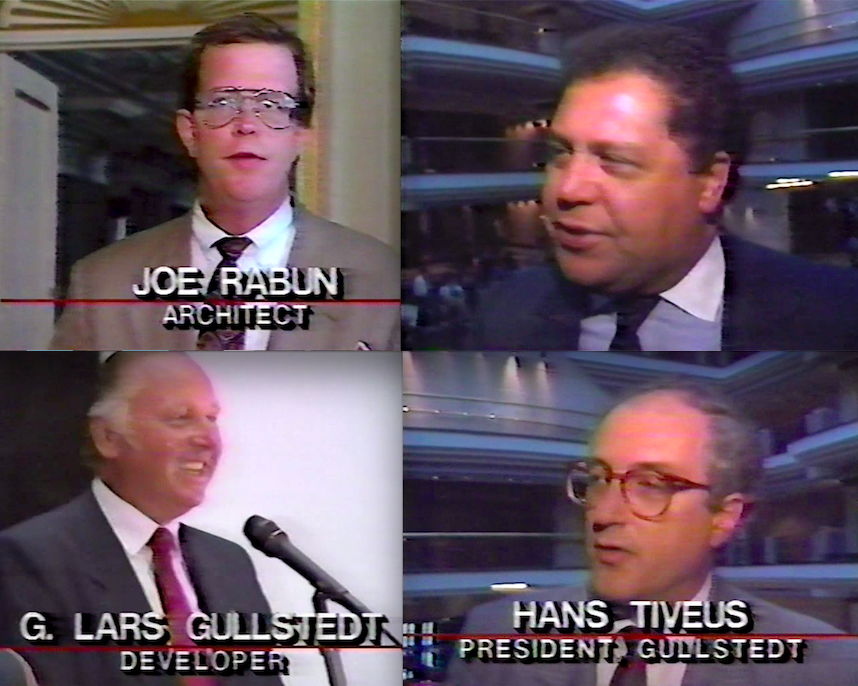

Then that same reporter, Jim Kaiserski, promised to spotlight the elephant in the room: a ruddy-faced European in a red tie who barely spoke English.

“We’ll have more on the mysterious Swedish man behind all of these plans,” said Kaiserski, “coming up at 6 o’clock.”

Clockwise, from top left: Rabun being interviewed in a vacant Biltmore; Mayor Jackson extolling the project's virtues moments after it was unveiled; and the two Swedish heads of Gullstedt Gruppen.WAGA 5; compilation, Urbanize Atlanta

Clockwise, from top left: Rabun being interviewed in a vacant Biltmore; Mayor Jackson extolling the project's virtues moments after it was unveiled; and the two Swedish heads of Gullstedt Gruppen.WAGA 5; compilation, Urbanize Atlanta

Thirty years after GLG Park Plaza went public, capturing imaginations amidst Atlanta’s second skyscraper heyday, the story of its creation is a cautionary tale as to why the “construction miracle” never even broke ground. But it’s also a story about unlikely friendships, outsized ambitions, and good old-fashioned hustle. The setting was a city gutted of population and pockmarked with blight and vacancies—yet eager to rise up for its time on a global stage. And the billion-dollar big idea, if only for a brief time, was proof Atlanta had arrived.

…

The enigmatic Swedish billionaire G. Lars Gullstedt—namesake for the “GLG” acronym—might be the money man that most Atlanta historians associate with the megaproject.

But the idea was all Joe Rabun’s, an affable Atlanta architect still practicing today.

Raised in Mobile, Alabama, Rabun moved to Atlanta after graduating from Auburn University and earned his spurs working for revered local firm Jova/Daniels/Busy, before breaking off to start his own in 1975. By the early 1990s, Rabun Architects had designed the brutalist Mobile Hilton, prestigious InterContinental Hilton Head, the Atlanta Airport Hilton, and Westin Buckhead, among other projects.

Rabun’s group was working on designs for a property on 14th Street in Midtown when Gullstedt’s company, Gullstedt Gruppen of Stockholm, bought that land sight unseen. The architect got a call that Gullstedt was heading to Atlanta for the first time with his company president, Hans Tiveus, and wanted to discuss possible plans.

A born risk-taker, Gullstedt had grown up on a farm, founded a construction company, and later built a development firm that made him one of Sweden’s wealthiest businesspeople. He developed a suburban, mid-rise office park outside Stockholm called GLG Center that all but invented the model and earned him acclaim—such a success that bankers were lining up to finance whatever he touched next, and Gullstedt found himself dining with kings and queens. In Atlanta, Gullstedt saw a fresh, welcoming slate with a global airport, tons of growth potential, and far more liberal zoning rules than Sweden.

Rabun recalls walking Gullstedt—dapper and full of life, as always, but not even remotely conversational in English—into his conference room, with Tiveus acting as interpreter. He asked the Swedes a simple question about the 14th Street site: “What do y’all really want to build on this property?”

They looked at each other, conferred for a while in Swedish, and replied in unison: “The maximum!”

That project would become Midtown’s landmark, 53-story Four Seasons Hotel Atlanta (the city’s first 5-star hotel), and the initial meeting had gone so well, it was understood that Rabun would be Gullstedt’s architect moving forward.

…

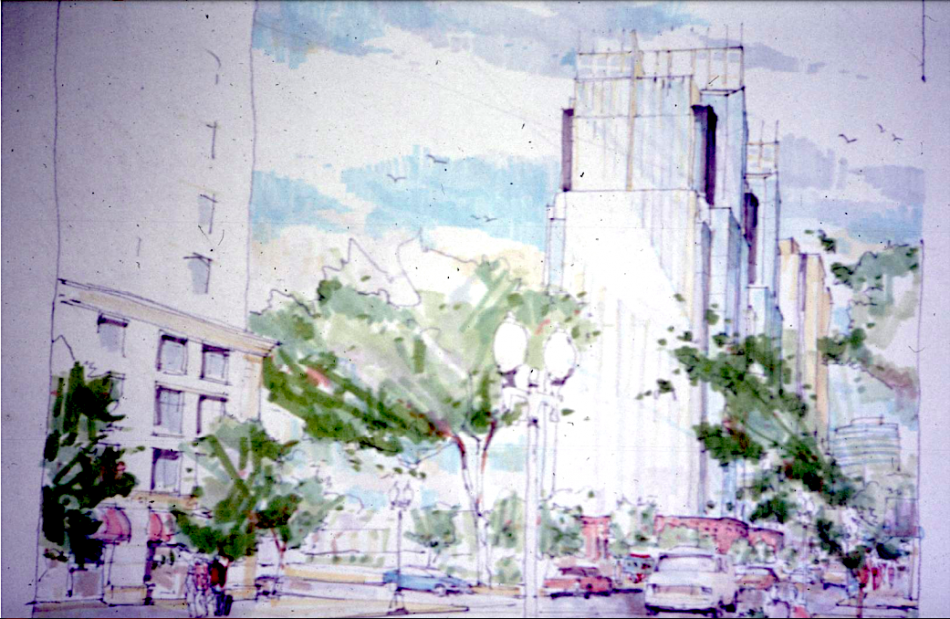

As the hotel was rising, Gullstedt started poking around about an investment building on 10th Street. Rabun went to investigate and just happened to notice that First Baptist Church of Atlanta had put its four-block property up for sale in hopes of decamping to the suburbs. That section of Midtown felt forgotten in those days, a landscape of dilapidated parking garages, underused small-scale buildings, an ocean of surface asphalt lots. Visitors to the Biltmore, which had been vacant for a decade, would often find cigarettes still burning from squatters who’d been spooked and ran. Rabun looked around that day, and a lightbulb went on. He turned to Gullstedt and said: Just think of how amazing it’d be if you took this whole area.

“We just kept getting into it, and into it, and thought, ‘God, it’d be great if you put a park in front of the Biltmore, build it out to Peachtree [Street] with parking underneath it and very nice buildings all around the sides,” says Rabun. “And then connected the roadway of 5th Street back into the bridge going over to [Georgia] Tech. We just developed the plan over months. We started drawings without showing [Gullstedt], and he was curious, kept asking.”

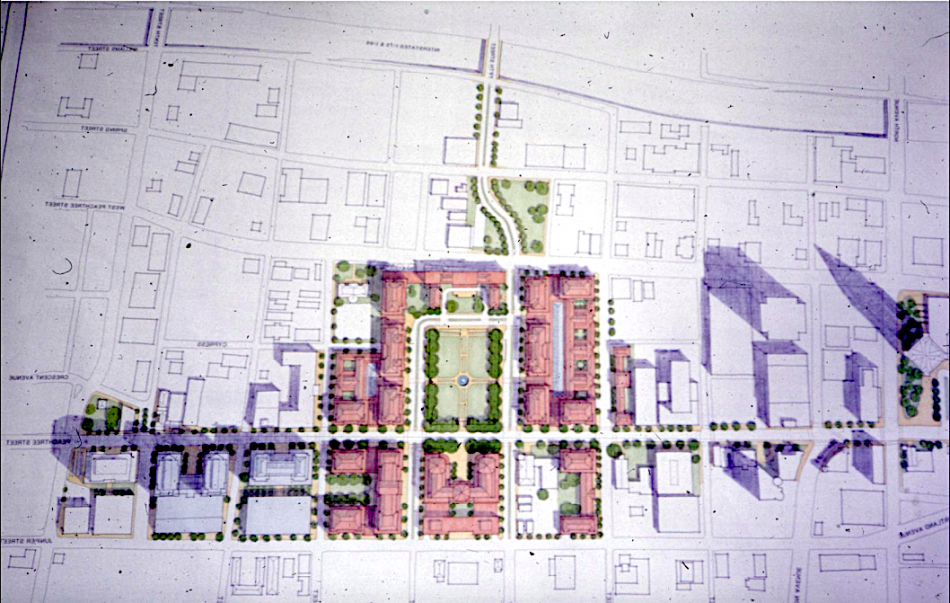

Early watercolor sketches for GLG Park Plaza in Midtown, published here for the first time.Courtesy of Joe Rabun

Early watercolor sketches for GLG Park Plaza in Midtown, published here for the first time.Courtesy of Joe Rabun

A sketch of the project's scope, with a central park bookended by the Biltmore and Peachtree Street.Courtesy of Joe Rabun

A sketch of the project's scope, with a central park bookended by the Biltmore and Peachtree Street.Courtesy of Joe Rabun

Rabun also started working his connections. He called a pal in commercial real estate, Bruce Gallman, and said he needed to assemble about 50 parcels from 39 different owners in the heart of Midtown. Gallman’s reaction: “Are you crazy?”

But Gallman also worked with Parking Company of America, a group led by Manuel Chavez—one of intown’s biggest landowners at the time. And everybody in Midtown knew that. So when Gallman came asking if a certain landholder was willing to sell, it was assumed that Chavez was up to his old tactics of buying land for parking lots in order to sit on it. And when Chavez made an offer, the logic went that you’d better take it, or he’d walk. In fact, some landholders were so eager to offload they called Gallman back and countered with lower asking prices to ensure the deals happened.

On the eve of GLG Park Plaza's storied unveiling, 11Alive's Bruce Erion hawked the skies, guessing where the project might be built around the Biltmore.11Alive

On the eve of GLG Park Plaza's storied unveiling, 11Alive's Bruce Erion hawked the skies, guessing where the project might be built around the Biltmore.11Alive

As Gallman recalls today, they got the Biltmore under contract for $1.65 million. The huge church property for $40 million. Eleven full city blocks for $97 million total. And every single transaction was top secret. If word would have leaked that a European tycoon was snooping around, it all would have fallen apart, as property owners would have demanded the world.

“Everybody thought it was [Chavez] buying property, so it was the perfect disguise,” says Rabun. “Nobody knew what we were doing. Nobody.”

All the while, Gullstedt was funding the transactions with borrowed capital from Swedish banks—easy money, no problem.

…

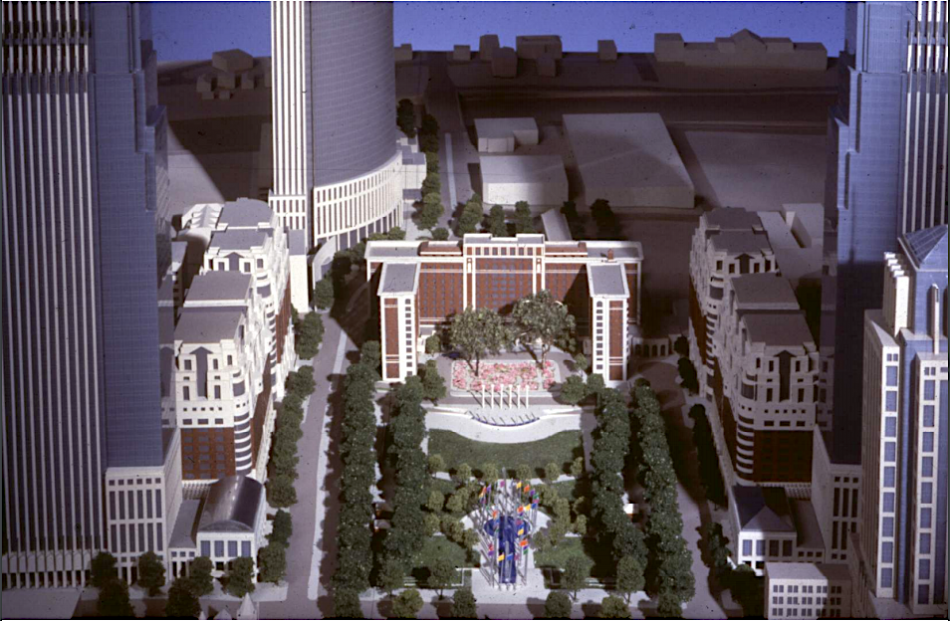

Rabun reached out to a professional model-building company and saw their vision materialize in a glorious, futuristic work of Styrofoam, big as a king-size bed.

Beyond the Biltmore and greenspace, GLG Park Plaza was to be a half-dozen towers of various heights spanning from Seventh to Third streets, and from Juniper Street almost to the downtown Connector—some 50 acres total.

The most prominent feature would be twin 64-story towers rivaling Atlanta’s tallest building today, Bank of America Plaza, and lording over residential Midtown and all points east for miles. It would entail up to 20 million square feet of residences, offices, retail, and hotel space. The rough timeline called for 15 years between groundbreaking and completion. By that time, as Gullstedt’s thinking went, America’s early 1990s recession (like Atlanta’s 20-percent office vacancy rate) would be a faded memory, and his billion-dollar baby would be large enough to accommodate full corporate relocations, the way Midtown is in fact doing right now.

The elaborate GLG Park Plaza model, as seen from a vantage point looking east, toward Piedmont Park.Courtesy of Joe Rabun

The elaborate GLG Park Plaza model, as seen from a vantage point looking east, toward Piedmont Park.Courtesy of Joe Rabun

After a year of assemblage victories, the team knew they’d have to make plans official and public if anything was to open in time for the 1996 Olympics. Rabun had a trusted ally in the city’s zoning department, the late Bill Kennedy, who kept everything quiet until he helped arrange a meeting with Mayor Jackson, who was blown away and giddy at the prospects of a splashy press conference. Rabun, meanwhile, was so meticulously calculating costs, spreadsheets on his office walls grew to 15-feet long.

It’s huge, but extremely doable, Rabun was telling his confidantes. It’s going to work. It’s flat out going to work!

The press conference had barely ended, and newscasters were declaring that the mixed-use colossus would dwarf John Portman’s iconic downtown creations. Kaiserski, the WAGA 5 reporter, observed: “Everyone at City Hall this morning gathered around the scale model of GLG Park Plaza as if they were approaching some kind of shrine.” And Tiveus’ project description that day sounded downright prescient: “We would like to have one place where you can live, work, entertain, shop, whatever—and less dependence on automobiles.”

The precise moment GLG Park Plaza went public, garnering uproarious applause at Atlanta City Hall.WAGA 5

The precise moment GLG Park Plaza went public, garnering uproarious applause at Atlanta City Hall.WAGA 5

In summation, Kaiserski offered: “The worst part of Atlanta, the developer says, will become the proudest part of Atlanta,” followed by an anchor’s optimistic recap: “[Gullstedt] rolled into town in a depressed real estate market, got the Four Seasons off the ground when many said it couldn’t be done, secretly acquired much of Midtown, and [today] announced a development of epic proportions.”

Still, longtime 11Alive reporter and anchor Brenda Wood offered a more sobering assessment: “The announcement came as a shock to many people who say downtown is in a real estate depression right now.”

Rabun, observing quietly in the wings, watched as the awed crowd literally applauded the model. Even rival builders were impressed, with the exception of “one old blueblood Atlanta developer” who called the vision “poppycock.”

…

A single phone call—a snap in the annals of city history—and it was all over.

By June of 1993, with pre-construction work still pressing forward, Gullstedt’s company had moved into Midtown offices next to Rabun’s. The architect knew it was a bad sign that authorities were raiding the developer’s offices and confiscating everything of value, even his car keys.

“It wasn’t working out over in Sweden, and they just put [Gullstedt’s] lights out—one day, that’s it,” says Rabun. “If he could have worked out things with bankers the way Portman did back then, we’d be sitting in the middle of [GLG Park Plaza] having this conversation. That’s where our office would have been. But I think [Gullstedt] just didn’t like bankers.”

The Swedish banks, facing a credit crunch, came calling on loans Gullstedt couldn’t pay back with so much of his wealth tied to real estate. The banks declared Gullstedt bankrupt, took ownership of all those Midtown acres and the Four Seasons, and appointed an executor in Atlanta, who gathered Rabun and the rest of the team in a room and said: “To you, I am Lars Gullstedt now.”

Then the real Gullstedt’s predicament got even worse. Swedish government officials who’d been investigating his businesses charged him with insurance fraud, and in 1997 had Gullstedt arrested.

...

Older, quieter, and humbler, Gullstedt revisited Atlanta in 2010 to promote the condensed English version of his book, fittingly titled, “When the Bank Helped Itself.” He met for lunch at the Four Seasons with Rabun and veteran Atlanta business journalist Maria Saporta, who noted that Gullstedt was eventually cleared of all wrongdoing, according to his book. But being declared bankrupt in Sweden all but blackballed people from getting back into business, and Gullstedt’s empire had long since dissolved. “The banks took everything,” Gullstedt told Saporta. “It’s very difficult to start again.”

Still, Four Seasons employees thanked Gullstedt that day for the “castle” he’d created, as the developer called Midtown’s growth “fantastic”—including the buildings Georgia Tech and so many private companies had erected on ground that used to be his.

The skylines of Midtown and downtown today, and an approximation of where GLG Park Plaza would have stood.Courtesy of Conner Christie; customization, Urbanize Atlanta

The skylines of Midtown and downtown today, and an approximation of where GLG Park Plaza would have stood.Courtesy of Conner Christie; customization, Urbanize Atlanta

That lunch meeting was the last time Rabun saw Gullstedt alive. He died just shy of age 80 in 2015 while living in South Florida.

Looking back 30 years, the architect recalled this month the good times he had while the GLG Park Plaza dream was percolating—the visits to Sweden, zipping around on Gullstedt’s boat, staying at his castle-like, idyllic home. But Rabun’s tone changed when asked if he ever looks across Atlanta’s skyline and pictures what isn’t there, what could have been. He’s never been wanting for clients, and he quickly moved on, but he’d also devoted almost three years to something that so suddenly fell apart.

“It was terrible—just terrible—what a bummer,” says Rabun. But then, more optimistically: “Things are happening in Midtown. There’s lots of substantial development all over that area now. It ended up being a cohesive, strong part of town.”

Whatever happened, Rabun was asked, to that huge project model—that “shrine”?

His company kept the model in their offices for many years, it turns out, but eventually just threw it away.

• Recent Midtown news, discussion (Urbanize Atlanta)