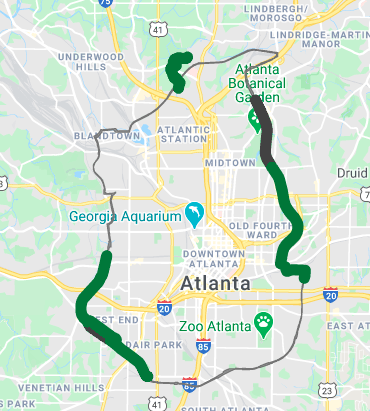

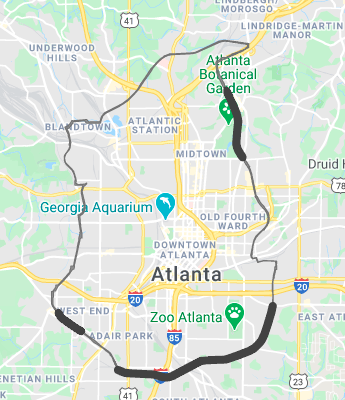

For the better part of a decade, the two primary knocks against the Atlanta BeltLine have been paradoxical: On one hand, critics complain the famed 22-mile urban reclamation project has drastically driven up costs of living for renters and homeowners alike, while squashing affordable housing.

On the other, they gripe about the BeltLine taking so damn long to build.

To help remedy the latter issue, BeltLine officials announced bombshell plans this month to scrap the process of building out the multiuse loop one section at a time with Tax Allocation District funding, which is expected to fall $1 billion short of initial projections.

Instead, Atlanta City Councilmember Dustin Hillis (District 9) has introduced legislation for a new tax plan that backers say would thrust into hyper-speed design and construction of the $350 million of BeltLine work that remains.

Adopting the tax hike would mean the BeltLine is completed not only in this generation, but at least a year before the longstanding goal of 2030.

But naturally, not everyone’s overjoyed at the prospects of forking over more tax dollars. Especially in the throes of a global pandemic.

In a nutshell, the property tax funding mechanism, known as a Special Service District, would cover properties within a half-mile of the BeltLine corridor. Those required to pay more taxes would be owners of restaurants, shops, pubs, and other commercial properties, along with holders of multifamily properties such as apartment complexes. Plans call for them to fork over an extra two-tenths of a penny per dollar in assessed property value.

As Hillis explained to Urbanize Atlanta, that would translate to $800 annually per every $1 million your restaurant building, gas station, or boutique apartment is deemed to be worth.

The positives of a finished BeltLine, as project leaders have noted: a $10 billion economic boost to the city and 50,000 permanent jobs, nearly twice as many as originally projected.

Also catalyzed by the SSD taxes, per their estimates: $50 million in additional affordable housing funds; $7 million in extra support for small businesses; and $12.5 million to help keep “legacy residents”—longtime citizens who’ve typically ridden through a neighborhood’s ups and downs—from being pushed out by rising prices.

Hillis was inspired to sponsor the legislation after seeing not a single yard of BeltLine built in his Northwest Atlanta district over the years. He’s concerned that his local section of hypothetical BeltLine would be the last to happen, as plans currently suggest, and he wants to ensure guaranteed funding for all remaining gaps.

“At this point, they don’t even know the route [the BeltLine] will take,” said Hillis of his district. “I want to see that change, and the sooner the better.”

In Hillis’ corner is BeltLine visionary Ryan Gravel, who penned a recent AJC column in favor of the SSD as a means of expediting the physical BeltLine and its transformative potential.

“To realize the full vision of the Atlanta BeltLine, and to make sure that it includes everyone, we must finish what we started,” wrote Gravel. “That requires sustained attention and investment from a variety of public, private, and philanthropic sources in all aspects of the project.”

The counterpoint came recently from Jim Fowler, president of the Atlanta Apartment Association, a metro-wide group with 1,450 member companies that control 430,000 rentals.

Fowler argues that any tax hikes for multifamily property owners will only trickle down to renters—a population segment disproportionately struggling with job losses and other pandemic tolls. In another AJC column, Fowler calls the tax plan “the latest potential blow in the ever-growing struggle to provide housing affordability in our city."

“The proposed BeltLine SSD,” Fowler continues, “would tax apartment properties but continue to exclude the tens of thousands of single-family homeowners who benefit financially from proximity to the Beltline.”

Perhaps the harshest criticism for potential SSD taxes has come from the Old Fourth Ward Business Association and individual proprietors in that neighborhood, which has seen massive influxes of investment as the BeltLine’s Eastside Trail materialized.

Brandon Ley, cowowner of Joystick Gamebar and Georgia Beer Garden on Edgewood Avenue, told Intown Atlanta he felt “completely ambushed” by the SSD proposal in that no outreach to commercial property owners had been conducted before the BeltLine’s plans made headlines.

Hillis said a government work session on the SSD legislation is tentatively scheduled for February 16.

“It would then come back to committee in late February for consideration,” Hillis said. “The soonest I imagine it reaching and passing full council is early March.”

Assuming the new tax plan is passed within the next few months, Hillis said, the bump in property taxes would be seen on bills issued in late 2021.

• BeltLine (Urbanize Atlanta)