After 20 years of Atlanta BeltLine planning and construction, the grassroots citizen group BeltLine Rail Now is collectively disappointed, shocked, and embarrassed that not a single mile of light-rail track or one train stop exists around the city’s fabled loop, its leaders say.

With a new administration installed in Washington D.C., and talk of transit and infrastructure dominating national headlines, BRN—often written with an exclamation point, BeltLine Rail Now!, for emphasis—believes a generational opportunity is afoot. And they fear the growing City of Atlanta might squander its chances for a robust transit network if meaningful action isn’t taken immediately.

BeltLine visionary Ryan Gravel and former city council president Cathy Woolard, a longtime transit advocate, founded BRN in 2018, after 71 percent of Atlanta voters approved an additional half-penny sales tax for More MARTA projects. Gravel and Woolard have stepped aside, but current BRN leadership feels MARTA’s 30-year timeline to implement all BeltLine rail transit, which was integral to Gravel’s original concept, is unacceptable.

For its part, MARTA has allocated funding and approved a feasibility study this month the agency says will boost the chances of federal transit dollars being channeled to Atlanta.

How the trail and train might commingle in more forested BeltLine sections. Atlanta BeltLine Inc.

How the trail and train might commingle in more forested BeltLine sections. Atlanta BeltLine Inc.

BRN, helmed by seven board members, has staged protests, written op-eds, attended numerous meetings en masse, and just before the pandemic, led a petition drive that delivered 10,000 signatures to Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms’ office, calling on the mayor to lead hastened transit implementation. None are paid for their work.

This week, Urbanize Atlanta caught up with three BRN board members to talk transit during what they feel is a historically critical year.

BRN! board members participating in a recent interview, with the organization's chair, Matthew Rao, at top. Urbanize/ABI

BRN! board members participating in a recent interview, with the organization's chair, Matthew Rao, at top. Urbanize/ABI

They are BRN chairperson Matthew Rao, a Georgia Tech-educated kitchen and bathroom designer by day; the organization’s outreach coordinator, Beth Smith; and a more recent arrival, Lawrence Miller, who chairs Adair Park’s neighborhood association and cofounded the Murphy Crossing Coalition to help ensure that BeltLine development includes what neighbors want.

…

Urbanize Atlanta: What’s your mission overall?

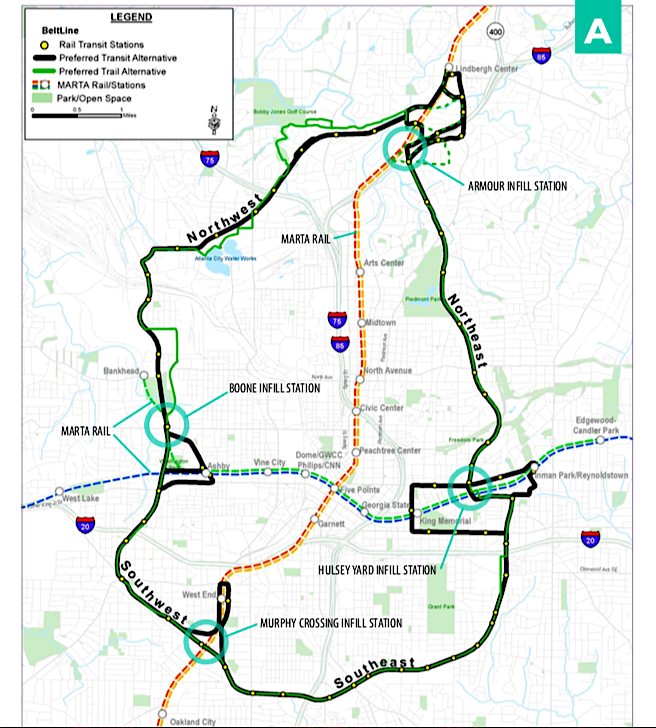

Matthew Rao: We’re focused on seeing that MARTA finish the BeltLine by 2035, the entire 22 miles; by 2030, we want to see the “J” finished, which runs from the Lindbergh area clockwise around to Bankhead Station. The J is about 15 miles.

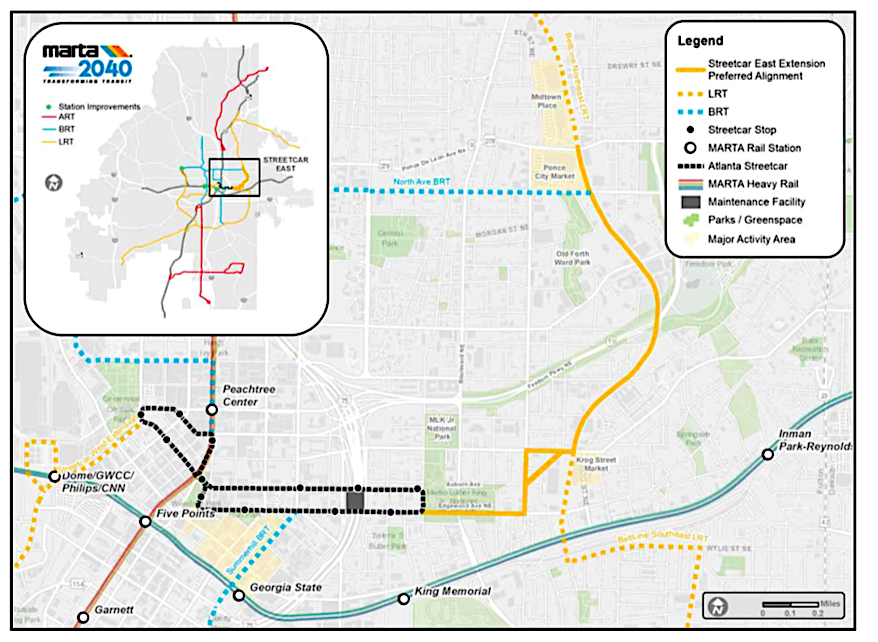

That includes building the streetcar extension to Ponce City Market within three years, because that’s the first project. [MARTA’s] timeline now is 2027, but experts tell us [the initial section] can be built in three. We’re focused on saying why can’t we get that section built right now, because it doesn’t require any federal funding; it [costs] $150 million, and More MARTA has raised over $200 million to date in sales taxes that have been paid, and they already started pre-engineering on this last October.

The full scope of MARTA's plans for 22 miles of BeltLine rail, including potential infill stations and existing heavy rail. The 15-mile "J" swoops down from near the infill station at top to the Bankhead stop at left. MARTA

The full scope of MARTA's plans for 22 miles of BeltLine rail, including potential infill stations and existing heavy rail. The 15-mile "J" swoops down from near the infill station at top to the Bankhead stop at left. MARTA

UA: Does the average Atlanta citizen citywide see BeltLine rail as being as crucial as you guys do—or even close to that?

Beth Smith: From my perspective, it’s an extremely complicated subject that’s not easily answered in short sentences and certainly not on Twitter. The average person might be under the impression that MARTA’s handling all of this. I would certainly have that impression if I didn’t spend so much of my spare time talking about this project with people studying highly complicated documents and helping translate them.

I came into this without any background in transit activism but recognized the equity that’s at stake here. That seems to get lost in so many of the conversations. I get emotional about the situation because we have an opportunity most cities don’t, and it would sincerely be a shame if we just let it slip through our fingers. You’ve got to start building it, because you can’t develop out all the property along the BeltLine and then decide to start implementing the transit.

UA: Or what?

Smith: We’ve seen what happened to the Old Fourth Ward, people living with terrible traffic congestion because they were promised by Atlanta that transit is coming. We built the density and continue to build it because we have to—our population is exploding. But we don’t have adequate transit solutions. People are under the mistaken impression [light rail] is being implemented as quickly as possible. Our organization has every reason to believe that’s simply not the case, based on talking with experts and looking at successes in other cities. If you build up this city and don’t give people the opportunity to live their lives without a car, we’ve failed.

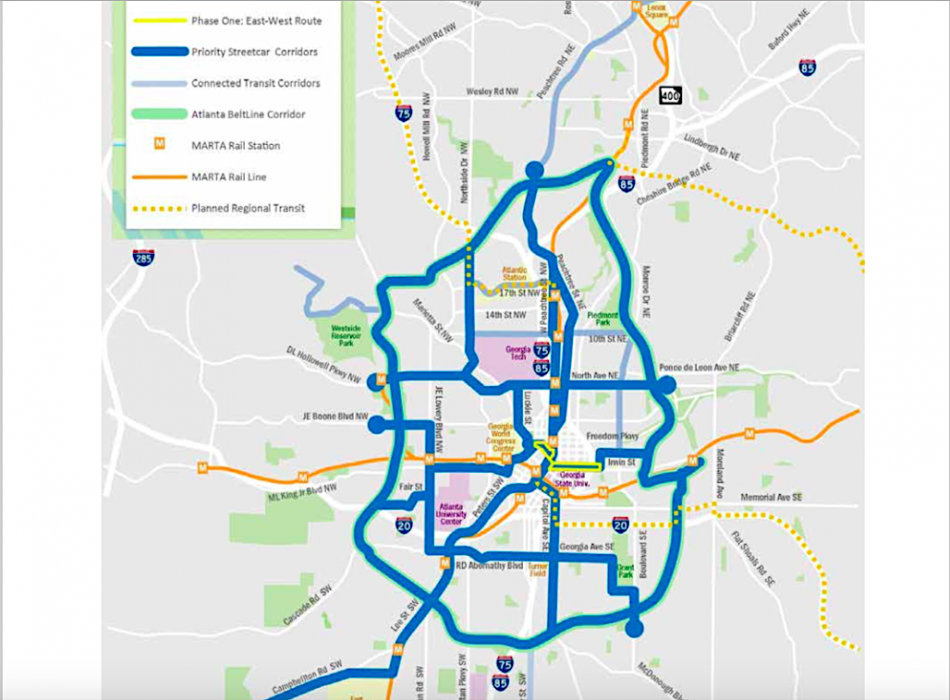

The ultimate plan for building out the Atlanta Streetcar system with transit connections, stretching at bottom left to Greenbriar Mall. MARTA/ABI

The ultimate plan for building out the Atlanta Streetcar system with transit connections, stretching at bottom left to Greenbriar Mall. MARTA/ABI

UA: [To Miller]. What about [BeltLine Rail Now’s] presentation, what they brought to the table, made you feel that rail was crucial in Southwest Atlanta on the BeltLine?

Lawrence Miller: That’s simple. This city is divided by the freeways, the highways, the big roads, and they were designed that way to destroy predominantly Black neighborhoods. This is a historical fact. I discovered that the idea of rail was introduced in the very beginning by Ryan Gravel. It’s complete by having rail and the concrete. But all we ever heard about down this way was the concrete sidewalk. I’m originally from New York—I know how important rail is.

UA: From what you’re hearing in Southwest Atlanta, the conversations you’re having, what collectively is the feeling specifically about rail coming in?

Miller: To be blunt, it’s going to encourage more white people to move down this way, which will move more Black people out. The problem is there’s an answer to that that no one’s brought up: The BeltLine and Invest Atlanta have programs that encourage Black and brown people to buy their homes in these neighborhoods.

[If BeltLine rail is built] people here could use it to get to higher-paying jobs in other parts of the city. And you could use it to leave your damn car at home so you can go to Edgewood and party and not have to worry about the price of Uber or Lyft. While it may seem like [rail transit] is more of a gentrification tool, that’s one reality, but not the only reality.

I’m handicapped, and those who don’t drive for legal reasons would have the ability to see some of these other neighborhoods in a way we can’t right now. I’m nine minutes’ walk from the West End—right across the tracks—but I cannot walk there. Lee + White is seven minutes away, but I can’t walk there. The entrance to the Westside Trail is three minutes away, and I can walk there.

I don’t want to take an Uber to the West End MARTA station, just so I can get on a train.

The look of a potential Eastside Trail stop near Highland Avenue. Atlanta BeltLine Inc.

The look of a potential Eastside Trail stop near Highland Avenue. Atlanta BeltLine Inc.

UA: The phrase your group uses is “the fierce urgency of BeltLine rail.” Why is right now critical? We’re coming out of this pandemic, and there’s federal money floating around, but is there a broader timeliness to this people should be paying attention to?

Rao: No question about it. The stars are never going to align better than they are right now for the Atlanta BeltLine and every other transit project in Atlanta.

We have a president who proposed this infrastructure bill with $85 billion in it for transit, and $20 billion more for repairing the damage that redlining and interstate highways have done to America’s cities. There’s a congresswoman in Nikema Williams [GA-05] who sits on the transportation committee; there’s a transportation secretary [Pete Buttigieg] who a couple of weeks ago called out the Atlanta BeltLine by name as a project where they could fund light rail. There’s a senator [Raphael Warnock, D-GA] whose church sits on the first segment that can be built.

I just don’t see how it could possibly be better for us right now. The problem is us. Are we ready to receive what’s there to take?

UA: It’s written in some of your literature that we’re either at the crux of a “tremendous rebirth or demographic meltdown.” We’re at a crossroads, as you see it?

Rao: Absolutely. And I see 2021 as really a watershed year for one future or another, because we’re electing new city council people and a new mayor.

We believe it’s the mayor and our city council who can express the desire and will of the citizens of Atlanta—the people paying the More MARTA tax—in terms of priority and an urging to get going. When you think about it, we’re really almost 20 years in [since the BeltLine’s inception], and we don’t have a real schedule that results in much of this before the end of this decade.

When we did our [white paper research], we learned just how far and fast other cities that were on fire about an idea went. In Portland and Denver, what they were able to do when the will of the government and citizens, and the receptive transit agency, came together … Even a program in Denver that fell short has resulted in nearly 100 miles of street track in the form of light rail or commuter rail in just about the same amount of time we’ve been talking about the BeltLine. Our ambition is low here for the kind of city we say we want to be.

UA: Do you get the feeling MARTA shares the sense of urgency now for creating BeltLine rail to even remotely the degree you do?

Rao: I would say, sadly, the answer’s no. And that’s because of the timeline they’ve proposed. They have conceded that more funding sources are necessary, for the whole More MARTA program. They seem to be piggy-banking the money for More MARTA programs and waiting for one fell swoop in the future.

The timelines are so long as to be laughable. Longer than the [BeltLine] idea has been around, it’s going to take MARTA to build 15 miles of rail [in the BeltLine corridor], four to Emory [University], and seven down Campbellton Road. It’s projected at 2045. That’s almost embarrassing. We really think that 2045 or 2050 is the same as saying, “Not at all.”

UA: Speaking of MARTA, the recent big news was the six-month feasibility study they’re doing [for BeltLine rail], costing $500,000. Do you feel it’s unnecessary?

Rao: We feel it’s questionable. We’ve asked for clarification from MARTA and we expect a high-level briefing from them within the next week or so. When the word “feasibility” was used, they really seem to be talking about whether they can build it at all. Because the outline of the rail gaps and talk about them leads one to believe they don’t know, even though they’ve affirmed light rail as the preferred alternative on several occasions.

Many people say you don’t need another feasibility study, but a study about what solutions to employ—and if that’s what they’re doing, we’re all for that. They’re not wrong in that different alternatives to get to there from here need further study. But it looks like a pretext to me for coming to a different conclusion, for this project that Atlantans have said they want.

More MARTA’s first light-rail project, Atlanta Streetcar East, is expected to extend the current streetcar line .8 miles from Jackson Street and build 1.4 miles of BeltLine rail up to Ponce City Market. MARTA

More MARTA’s first light-rail project, Atlanta Streetcar East, is expected to extend the current streetcar line .8 miles from Jackson Street and build 1.4 miles of BeltLine rail up to Ponce City Market. MARTA

UA: In a perfect world, what would you like to see happening between here and 2026?

Rao: We’d like to see them talking about how to satisfy ridership demand for the section they’ve already opened to Ponce City Market. And we’d like to see cranes and trucks and construction vehicles on the Southside Trail, building the BeltLine rail. In order to finish the J by 2030, we’ve got to get going right now. And more than one section can be built simultaneously, by the way. So in five years, we’d like to see construction from Bankhead to Wylie Street.

UA: People have been waiting so long for certain BeltLine sections to come in, I think there’s some reservation that once they start building rail next to it, they might have to close parts of the BeltLine. You’re confident all this you want can be built next to a fully opened BeltLine?

Rao: That’s a great question, and I’m not a construction expert. But if you have to temporarily close parts of the trail in order to build the reason for the project, that’s a temporary thing. And it’s a price I think people would be willing to pay in order to get what they’ve been promised delivered faster.

Miller: We voted 70 percent in favor of the More MARTA tax, and one big reason is we were told it would include rail. I cannot emphasize that enough. There’s no way we would have increased our own taxes if we weren’t going to see some tangible benefit. And for us, that meant rail.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

• MARTA takes step forward in bringing transit to Atlanta BeltLine (Urbanize Atlanta)

• BeltLine Rail Now! (website)